Body Double is a film that I often see written off as inferior to Brian De Palma’s most noteworthy efforts. And that’s a shame. Body Double is among the director’s most stylishly risk-taking films, combining classic Italian giallo with the creative high points of Alfred Hitchcock.

Released in 1984, Body Double also culminates De Palma’s attempt to push film noir and erotic-thriller conventions as far as possible within Hollywood’s R-rated boundaries. The result is a twisty, kinky exercise in escapist cinema that is far smarter than it gets credit for.

The film was De Palma’s biggest Hitchcock-inspired mashup/homage to date, following in the heels of his own Sisters (1972), Obsession (1974), Dressed to Kill (1980), and Blow Out (1981). Though these films often reference Hitchcock’s Rear Window theme of voyeurism, Body Double comes closest to fully expanding upon that story’s premise.

We follow the plight of struggling actor Jake Scully (Craig Wasson). On the hunt for work and a new place to live, Jake meets Sam (Gregg Henry), a fellow actor who offers him a housesitting gig. Jake is keen on the arrangement and graciously accepts. As he settles into his new digs, Jake begins making use of a telescope the homeowner left behind to spy on a mysterious neighbor prone to suggestively dancing in various stages of undress. Through his penchant for peeping, Jake becomes convinced that someone is stalking the woman. His attempt to help pulls him into a web of deceit and murder where nothing is as it seems.

As the plot crunch suggests, the film is a tawdry, horror-tinged nod to Hitchcock’s filmography, from Rear Window’s microcosmic spying to the more directly sexual peephole in Psycho. When Jake Skully shifts from watching to stalking, hampered by his own problems with claustrophobia, the movie references Vertigo and its lead’s weakness to acrophobia; the over-arching plot setup is also similar.

De Palma’s references/homages aren’t limited to Hitchcock. A brutally phallic scene involving a large power drill recalls Michael Powell’s controversial Peeping Tom (1960) and De Palma’s own splatter-film showstopper – involving a chainsaw — in his profitably splash-making previous film, Scarface (1983).

Therein lies the reason some critics didn’t connect with Body Double, labeling the picture as derivative and excessive. Notably, the influential critic Pauline Kael, who up to then had championed De Palma almost to the point of critic-auteur symbiosis, took a harsh turn. Kael’s review said “the movie is like an assault on the people who have put De Palma down for being derivative. This time, he’s just about spiting himself and giving them reasons not to like him.” (On the opposite end of the spectrum was critic Roger Ebert’s positive take, which was willing to meet the film on its own terms, even when transmutating into a video for the Frankie Goes to Hollywood song “Relax.”)

While the film is certainly over-the-top and wears its Hitchcock influence on its sleazily unbuttoned, porny silk-shirt sleeves, Body Double has its own unique style, a strong point of view, and plenty to say. De Palma merely uses his inspirations as a starting point, charting his own course from there.

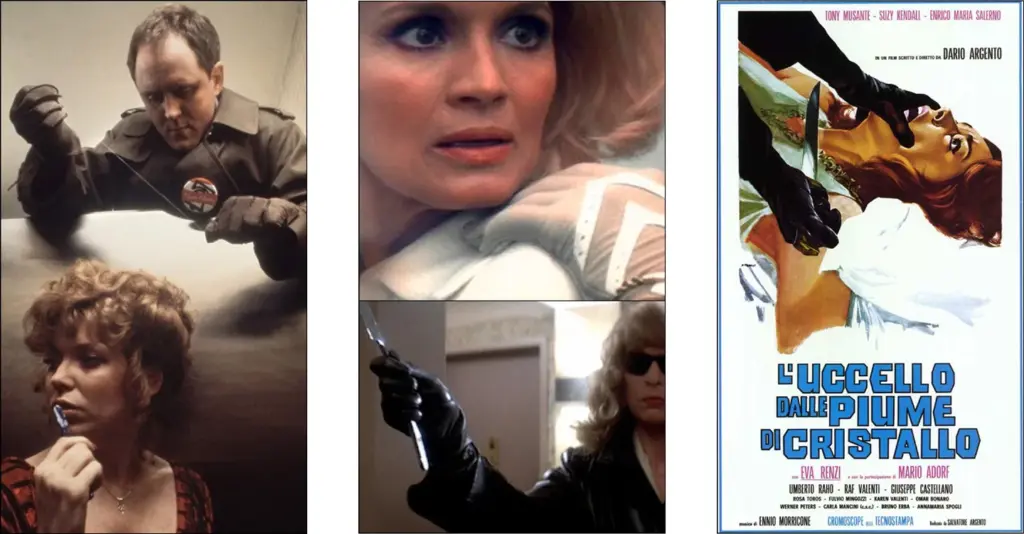

The influence of Italian giallo films

Speaking of the director’s inspirations, one of De Palma’s other core influences is the giallo output of Italy from the 1960s and ‘70s, of whom the best known-director director is Dario Argento. There are ample references to that cinematic sub-genre in Body Double. Giallo films, which drew from both the Italian neo-realist movement and classic film noir, are murder mysteries known for their outlandish setups. These often involved a gloved killer whose identity is only revealed after copious amounts of sex and violence.

Once you’re aware of the giallo influence on De Palma’s films of the time, it’s hard to miss the connection – particularly in details like leather gloves. Viewers may recall killer John Lithgow’s prominent black gloves in Blow Out; and that De Palma’s Dressed to Kill includes a scene when a glove is seductively waved as a sexual invitation to Angie Dickinson’s character at the conclusion of a Vertigo-like art-gallery scene.

Body Double’s big reveal parallels a key plot point from the 1969 giallo Double Face (note the similar titles). The De Palma film’s ongoing surrealist tone, stylized violence, and eroticism mirror the gialli genre’s dreamlike blurring of fantasy and reality. If you watch Giuliano Carnimeo’s The Case of the Bloody Iris (1972), for example, the swirling combination of sex, violence, and surrealism establishes a disorienting mood very similar to Body Double.

Hitchcock references are everywhere

As for the Hitchcock references, even the most casual of film fans are likely to recognize them as Body Double plays out. Lead actor Craig Wasson spoke with the Dutch fanzine Schokkend Nieuws a while back and touched on Hitchcock’s influence on De Palma, saying, “The whole movie was also a salute to Hitchcock. Go back to Hitchcock and you can see it’s all there.”

Wasson saw the influences up close. In addition to the aforementioned Rear Window and Vertigo connections, the modernist dwelling Jake housesits (the John Lautner-designed Chemosphere in Hollywood) bears resemblance to the Vandamm House on stilts (inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater) at the end of North by Northwest.

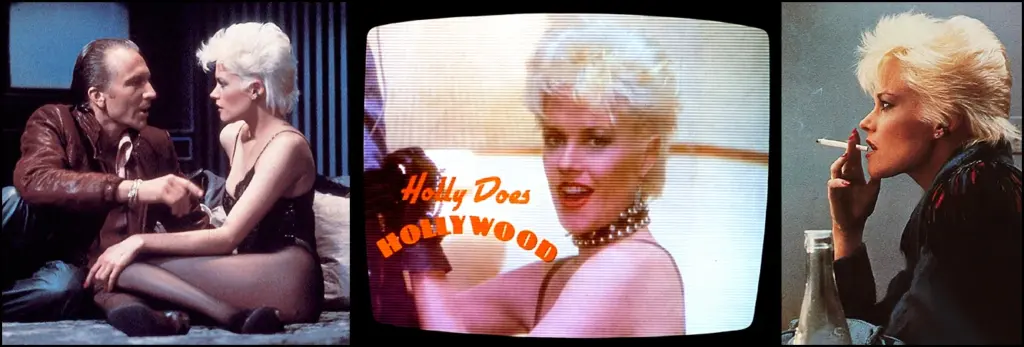

Especially spot-on is the performance by Melanie Griffith, for a character spit-take-laughably named Holly Body (just put “wood” in the middle?). Central both to the mystery and the theme, Griffith’s casting is not only canny, given that she’s terrifically natural and lively in the film; it also pays tribute to the actress’s mother, Tippi Hedren, famously featured in Hitchcock’s The Birds – and, unfortunately, subjected to Hitchcock’s obsessive misbehavior.

Body Double also has one of Brian De Palma’s signature visuals – where sunglasses are highlighted to amplify a character’s mysterious motives, to the point where the wearer seems inhuman, almost fly-like. Nearly every De Palma film has a variation on this image of shades, or black mirrors, reflecting back the protagonist’s own fear and guilt. The imagery most likely alludes to the spooky, watchful face of the policeman who pulls over Janet Leigh’s character in Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). For Body Double, De Palma uses the sunglasses effect not once, but twice – both for the object of desire, and that object’s killer.

De Palma wastes no time establishing Body Double’s themes and subtext, starting with the title card, set against the backdrop of a desert locale. The expansive landscape is revealed as a matte painting, which quickly rolls away to show that we are on a studio backlot. The setup reinforces an ongoing message: You can’t always believe your eyes, especially in Hollywood. Eventually we find that every character has secrets and hidden agendas. Even the film’s title even refers to an act of deception, both within the story and in cinema, especially self-reflexive cinema.

Among thoughtful performances is Craig Wasson as the flawed protagonist, Jake. In spite of occasionally appearing cynical, much of Jake’s arc revolves around his naivete. Wasson’s gullibility and weakness to temptation, tied to his innate decency, endears him to the audience but also inspires the kind of “Don’t do it!” reaction people have when a character in a horror movie descends into a dark basement.

In his interview with Schokkend Nieuws, Wasson spoke to Jake’s relatably damaged nature, saying, “We’re all messed up. We can be great and horrible. So, a guy grabbing some underwear out of the trash. It’s disgusting, but at the same time you might think: I don’t know. I might do that. It’s an embarrassing human trait.”

Body Double’s narrative, both twisty and twisted, is implausible yet engaging. It stands as a pulpy but sophisticated sendup of trash cinema and the film industry.