If you stand atop the headland that the Spanish explorers called El Malibu, the coastal rise above metropolitan Los Angeles, and look over the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, you may be able to see the hint of a small island through the haze.

Two hundred and ten years ago, in 1814, the people who lived there were massacred. They were killed not by Americans or Europeans, that old familiar story, but by other Native people, Aleuts from Alaska in the employ of a Russian fur company. With that act of violence, the Nicoleño people, the people of San Nicolás Island, disappeared from history.

But not quite. One of them, a young woman whom the Spanish later called Juana Maria, hid from the killing. The Aleuts left, occasionally to return to kill not people but seals, abundant on an island now mostly without human predators. Her brother, who had also escaped the massacre, was soon afterward killed by a pack of feral dogs, one of whom Juana Maria tamed. That dog was her only company over the next thirty years, for most of which Juana Maria lived alone on San Nicolás.

From passing ships, rumors reached the mainland about Juana Maria, a strange, almost spectral apparition dressed, barely, in blue-green cormorant feathers. A Spanish priest in Santa Barbara took an interest in this strange creature, and he sent a fur trapper to catch her. Eventually the trapper found her living in a cave, its mouth protected by a palisade of whale ribs, and transported her to the mainland. She was then in her late forties, the priest guessed.

Juana Maria—who reportedly was delighted by the crowds of people and the sight of horses, and who happily sang and danced for her visitors—lived only seven weeks more before dying of some unspecified illness, probably dysentery. She was buried in an unmarked grave. Her cormorant dress was lost in the Vatican Museum, while a few of her other things, housed in a San Francisco museum, were burned in the fires that followed the earthquake of 1906. Her island home was itself largely forgotten for decades, although it turned up in 1945 as a candidate for the atomic-bomb test that wound up being conducted at New Mexico’s Trinity Site.

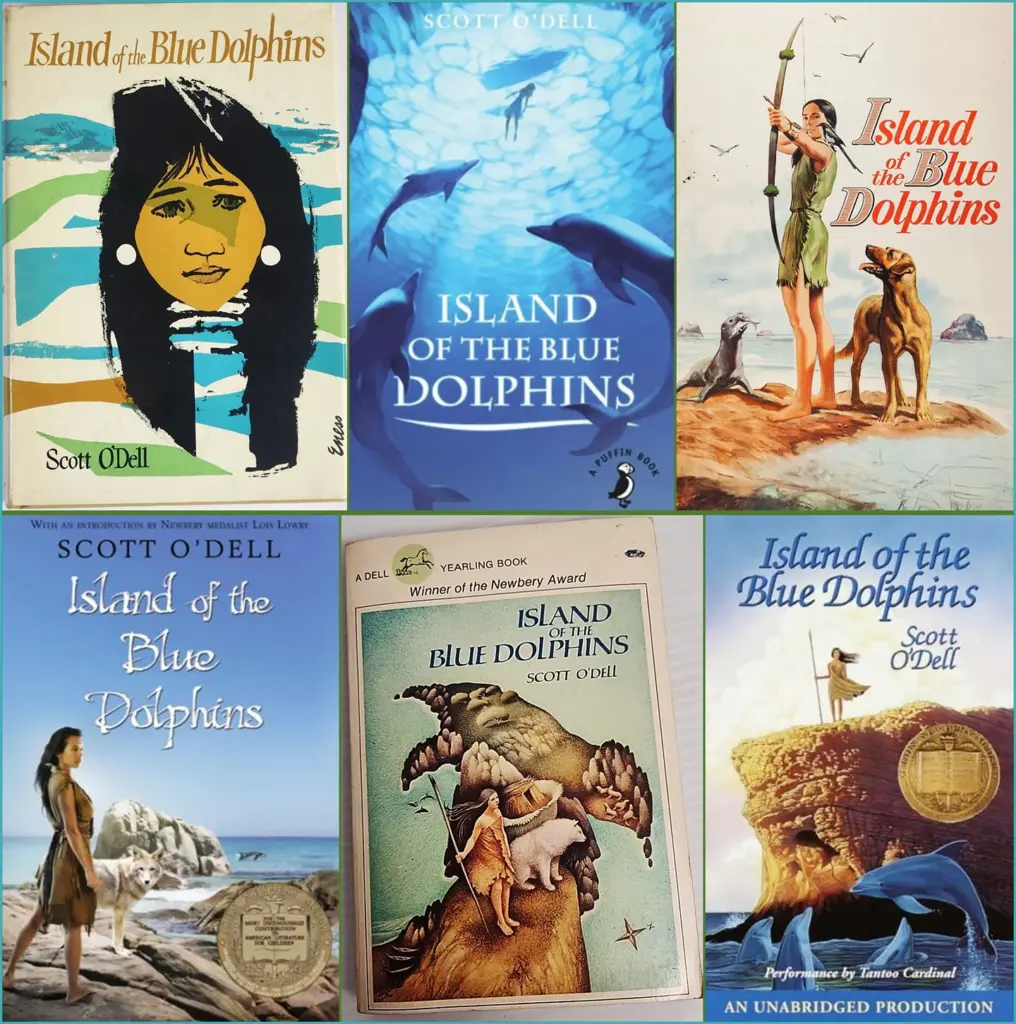

Juana Maria’s is but one of countless tragic stories of that time and place. It would have been forgotten had a writer named Scott O’Dell, who specialized in historically based stories intended for teenage readers, not found it in a book about Spanish California. In 1960, his novel Island of the Blue Dolphins was published, with Juana Maria now bearing the suitably exotic name Karana.

Since there were no surviving speakers of the language, we have no idea whether the name would have met with her approval, but when O’Dell got around to pitching a screenplay from his book, the script team, headed by a writer with only a few TV sitcom episodes to her credit, gave Karana a sort of me-Tarzan, you-Jane idiom, as when she addresses the murderous feral dog she would adopt: “Your eyes are like those of a fox, and as I don’t trust a sly fox I do not trust you either, dog. That would be a good name for you. I will call you Rontu. It means fox eyes.” Ugh, in other words, or, as the New York Times put it in reviewing the premiere, the producer “has kept the whole thing at elementary-school level.” (The book is more literate: “Before I fell asleep I thought of a name for him, for I could not call him Dog. The name I thought of was Rontu, which means in our language Fox Eyes.”)

Both O’Dell and the script team exercised creative license with other parts of the story as well. Pushing the Robinson Crusoe element, O’Dell gave Karana a sort of Friday in an Aleut girl about her age. The script team gave her extra-wizardly abilities to communicate with animals, from devilfish to otters and shorebirds, which doubtless would have earned her a visit from the Inquisition had she not died so soon after the Spanish found her. Still, there is a quiet, often elegiac feel to both book and film, particularly when Rontu dies, leaving Karana all alone (in the book, anyway): “I could feel his heart beating, but it beat only twice, very loudly, slow and hollow like the waves on the beach, and then no more.”

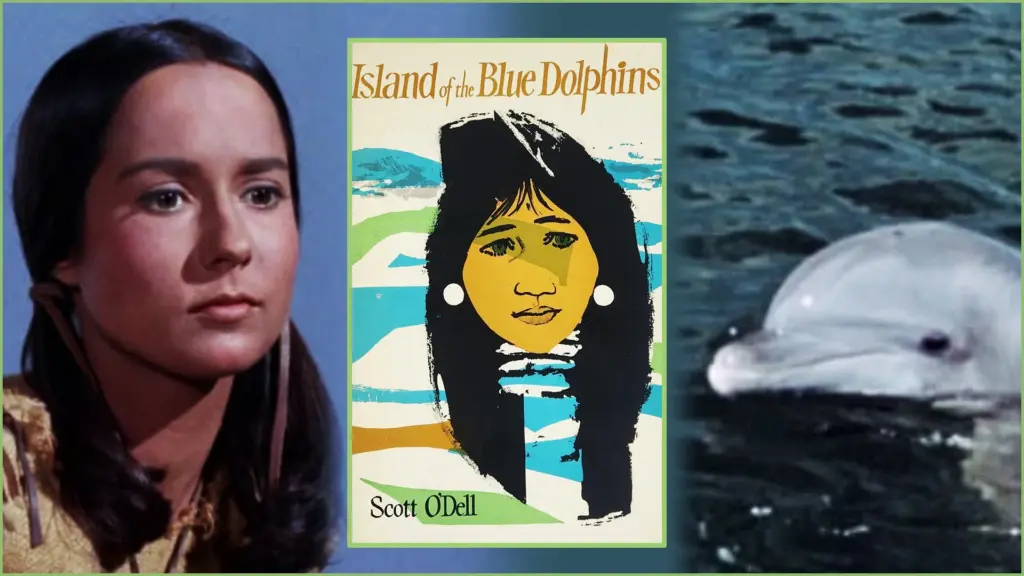

O’Dell’s book was well regarded, awarded a Newberry Medal, the highest prize for children’s literature in the land. Sixty-plus years on, it remains in print. In 1964 it was made into a film, with a young woman named Celia Kaye in the role of Karana. (She would later marry John Milius, who cast her as a voodoo-ish priestess in his entertainingly meatheaded film Conan the Barbarian.) Kaye was white, of course, as was almost everyone else in the film, two notable exceptions being a Mexican American who played a Nicoleño and a Catalonian who played a Spanish priest. Junior the dog, who played Rontu, was at least a dog, and while screen stardom eluded him, he enjoyed a late-in-life career revival in a short-lived TV series about military K9s.

For all its liberties and all the usual ethnic insensitivities of the time, the movie isn’t bad. Kaye won a Golden Globe, against serious competition, for best newcomer to film, and Island of the Blue Dolphins has even been reissued in BluRay. It played well at the theater, too, though Disney executives seem not to have liked the script, even with some of the harsher elements from the book toned down, and didn’t give the film much support. They gave the directing job to James B. Clark, who was known for animal films, having directed Flipper the previous year—there’s a dolphin tie-in for you—as well as Misty (of Chincoteague, that is) and worked on My Friend Flicka, two yarns starring horses. The animal connection, even allowing for the script’s magical inventions, may seem strange, but not so much when you consider that to this day Native Americans are administered by the Department of the Interior, which also manages wildlife, national parks, and the like.

Movies and television series such as Reservation Dogs, Dark Winds, Powwow Highway, and Smoke Signals, in which Indigenous people play Indigenous roles in front of the camera and are deeply involved behind the lens as well, are still too rare. Juana Maria’s story retains its power, and it would make a fine candidate for a remake from a Native perspective.