Last year, a series of life stresses wore me down to a pile of frayed nerve endings and haggard expressions, so I took refuge in comedy movies.

I know as much about the art of comedy as anybody else, which is to say, I like to laugh and that’s it. Analyzing jokes is a fine way to kill them. “Leave the comedy to the professionals,” they say.

But one comedy movie in particular got me thinking about how essential it is to build laughs around comedic foils: the reacting people who exist as a baseline reality for laughs to bounce off of.

The movie was Liar Liar, and 1997 flick I’d almost completely forgotten until it turned up on a streaming menu, and I reluctantly clicked on Jim Carrey’s head. The premise involves a neglected son whose birthday wish, through unexplained magic, forces his attorney father to speak only with 100% honesty for 24 hours. (Comedian Ricky Gervais attempted a similar premise, in reverse, for his 2009 movie The Invention of Lying, to modest effect.)

Liar Liar was the last in a series of Jim Carrey vehicles before he attempted more dramatic roles. Several of my friends don’t hesitate to tell me they loathe Carrey’s rubberfaced, anything-for-attention persona, and at his worst, yeah, he’s grating. I put Carrey in the same category as Tom Cruise: The less I know about his real life the better, but dang if he hasn’t made some entertaining flicks.

Whatever one thinks of Carrey, Liar Liar is a study in the effective use of comic foils. It’s far funnier than I remembered, and better than most of Carrey’s other comedies, with the exception of Dumb & Dumber.

But first, a quick look back at other comic foils.

What’s the heck is a foil?

According to a quick etymology search, the word “foil” derives from a practice of placing gemstones on top of shiny foil to make the gems shine more brightly.

The metaphor is certainly apt for the legendary comic foil Margaret Dumont. In the 1930s, Dumont often played a bourgeois female opposite the Marx Brothers. In movies like Animal Crackers, Duck Soup, and A Night at the Opera, Groucho Marx threw undermining zingers in her general direction, where she let them explode.

Without Dumont’s presence, Groucho would be riffing into a void, delivering his clever witticisms like a stand-up comedian in an empty room. Never breaking character as a humorless dowager, Dumont made the satire possible, representing the uptight society and its stilted mores. If you want to see a needle popping a balloon, you need a balloon. Dumont’s work, spanning a half-century, was lauded as making her “the fifth Marx Brother.”

We briefly see a Dumont-style foil in the Alfred Hitchcock thriller North by Northwest (1959), in the scene where Cary Grant purposely disrupts an auction because he needs to slow down some bad guys. While an auctioneer sells a statue to a crowd of well-heeled bidders, Grant blurts out, “How do we know it’s not fake? It looks like a fake!” Finally a woman (Les Tremayne) nearby leans over to tell him, “There’s one thing we know that’s not fake. You’re a genuine idiot,” to which Grant replies, “Thank you.” It’s one of my favorite scenes where the hero, justified in breaking rules, gets an equally justified reaction.

Think about your favorite comedy movie, and it probably contains scenes where someone disruptive embarrasses or irritates one or more others who are behaving normally.

It even works in small spaces, like in Dumb & Dumber, when Carrey and Jeff Daniels wear down Mike Starr, a mobster (posing as hitchhiker) sitting between them. “Want to hear the most annoying sound in the world?” Carrey asks, and then foghorns into his ear. Starr’s taking-things-seriously character creates the tension that the comedy then breaks.

A similar car scene occurs in one of my favorite comedy shorts, The Traveling Poet, a Chris Elliott piece that aired on David Letterman’s talk show in the mid-1990s. Elliott, riffing on the hitchhiking Leslie Howard character in a 1936 crime drama called The Petrified Forest, is utterly

obnoxious alongside the man giving him a ride, played by character actor Paul Dooley (in the classic film, the character was played by Humphrey Bogart). On his own Chris Elliott can be as funny as getting slapped with a fish, but alongside Dooley’s progressively deteriorating tolerance, the sketch becomes weirdly hilarious.

The Jerry Lewis Problem

When character actors, co-stars, extras, and other straight “foils” aren’t present, you end up with what we might call The Jerry Lewis Problem. I first encountered this as a kid, when a parent took me to see Lewis’s 1980 movie Hardly Working, where he plays a zany, incompetent dork failing at several jobs (waiter, cook, etc.). I remember watching Lewis mugging, stumbling around, crossing his eyes while making explosive growling sounds, and thinking to myself, “Why is this so painfully unfunny?”

The problem was that it was all him: The comedian painting hijinx without foils as his canvas.

This problem creeps into the third Austin Powers movie, with Mike Myers pulling diminishing “Yeah, baby!” returns out of a meager number of reacting co-stars. Among the worst “Jerry Lewis Problem” movies I’ve seen is The Jerky Boys: The Movie (1995), which attempted to adapt the popular crank-caller duo’s subversive antics to the real world, swapping actual dupes (the victims of their recorded phone calls) for low-grade actors exploding in unconvincing rage. In the Borat films (and Ali G/Bruno skits), Sacha Baron Cohen short circuited the comedy-foil issue by turning real people into Margaret Dumonts, a trick that required an army of lawyers and stacks of release forms to pull off. Without its victims (some far more deserving than others), the Borat shtick goes into the Jerry Lewis Problem zone faster than you can say “Va-jeen.”

Jim Carrey narrowly dodges the Jerry Lewis Problem

In the mid-1990s, Jim Carrey, in spite of his human-cartoon talents, was skirting Jerry Lewis territory with movies like Ace Ventura and The Cable Guy, the latter placing a crushing, uni-foil burden on Matthew Broderick. If you weren’t in the mood, the unrestrained nonsense became an assault. Bruce Almighty tried a Groundhog Day-like premise, setting up Carrey as a jaded TV newscaster who gains supernatural power over his personal reality.

The best approach to harnessing Carrey’s wildness was Dumb & Dumber, which smartly gave Carrey a softer-around-the-edges counterpart (Jeff Daniels) and an ongoing series of victims and foils. Even the bit parts gave audiences breathing room away from Carrey, like Fred Stoller punched out in a phone booth, Harland Williams as a state trooper drinking warm non-beer, Karen Duffy doing a spit take at a cork-lsain endangered owl.

Liar Liar completely cracks the code

Liar Liar is a similar case of where Hollywood got it right. Credit to director Tom Shadyac, with screenwriters Paul Guay and Stephen Mazur, for figuring out the best possible play for the Jim Carrey wildcard. The casting agents, Junie Lowry-Johnson and Ron Surma, also deserve particular praise, filling scene after scene with tonally perfect character actors.

Some of Liar Liar’s comedy is now dated (the native-American mouth-patting sound would likely whip up a social-media storm), but the movie remains a master class in how to use comedic foils, building a structurally solid platform of reacting characters, all lined up like bowling pins. Comedically, Carrey achieves the equivalent of a 300-score game, a final hurrah before he shifted to mostly dramatic roles throughout the late 1990s (culminating in standout Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind).

Even if you despise Carrey, Liar Liar is worth seeing just for its gallery of Margaret Dumonts. They deserve a tribute on their own.

Making the case: Comedy classic

It feels weird to sing the praises of any Jim Carrey comedy besides Dumb & Dumber, which at least had critic Pauline Kael’s stamp of approval. But Liar Liar is a worthy runner-up for top status.

What probably holds it back, for some, is the blatant “aww”-ness of the main character’s moppety son. As played by Justin Cooper, the boy’s emotional well-being repeatedly hinges on whether his workaholic daddy shows up for scheduled visits. Carrey, divorced from his son’s mother (Laura Tierney) due to his briefly alluded unfaithfulness, is constantly making bogus excuses. The unexplained magic that makes Carrey tell the truth for 24 hours serves as both punishment and a path to redemption (“I love my son!” he eventually proclaims). It’s an utterly contrived, dopey premise, but once you accept it, things start to click.

Liar Liar is a comedy-setup machine with one foil after another letting Carrey shine. There’s a Groundhog Day-like riff where Carrey repeats the same workday routine in two different ways: Dishonest and honest. When Carrey realizes he’s stuck telling the truth to everybody, he becomes his own comedic foil: An expedient-exaggerating Hyde overtaken by a cannot-tell-a-lie Jeckyll. There’s a mid-movie break as Carrey attempts to reconcile with his son and wife, as well as an unfunny doppelganger in his wife’s new suitor (Cary Elwes, hilariously burying his natural charisma in stilted earnestness). Numerous bit parts are like foil around the edges, ladling agreeable verisimilitude over the unbelievable premise.

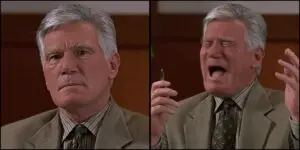

Then the big guns: Two massive comedy set pieces calibrated for maximum laughs. The first takes place in a board room, setting its sights on insincere, glad-handing corporate suckups. Carrey’s boss, played by the snakily sexy Amanda Donohoe, winds him up and sets him loose to insult his law firm’s president (Mitchell Ryan), who interprets the slams as a roast. The other takes place in the stuffiest of all settings, a courtroom, where oaths of truthtelling go hand-in-hand with lawyerly misdirection, and shattered decorum can lead to jailtime.

Any real-world trial lawyer can relate as the forcibly-honest Carrey says, “Your honor, I object!” and the judge asks, “And why is that?”, with the reply “Because it’s devastating to my case!” Also funny is Carrey answering a repeat offender’s call for legal advice by shouting, “Stop breaking the law, asshole!”

Liar Liar finishes with a legal twist, satisfying tie-ups of loose ends, and a standard Hollywood chase ending that, like Dumb & Dumber, sees Carrey falling and flailing on an airport runway. It’s undeniably stupid and yet clicks together nicely, then takes a well-earned victory lap with a credit roll full of amusing out-takes.

The out-take of Swoosie Kurtz pranking Carrey hammers home the reason Liar Liar works: Its Margaret Dumonts, its foils, are pitch-perfect and charming.

Quickly, here’s how Liar Liar stacks the deck so that Jim Carrey’s goofing is different from one scene to the next.

A study in foils: Female archetypes

The wife, Maura Tierney, affects the right tone of exasperation and concern. The power-boss, Amanda Donohoe, is a sexual harasser who serves both as foil and antagonist. Anne Haney, as the reliable secretary, is the confidant who’s above the B.S. of her job but remains professional. The competing lawyer, Swoosie Kurtz, has some of the best reaction shots in the movie, and she’s absolutely the best actress ever named Swoosie. As the bad mom and gold digger, Jennifer Tilly gives her husky busty best and brings a stylized comedy vibe of her own=. The attractive new employee in the elevator, Krista Allen, does a perfect friendly-to-peeved transition after a crudely honest comment about her breasts.

Groundhog Day-like repeat interactions, and one-offs

Liar Liar riffs on the difference between honest and dishonest small exchanges in several scenes, starting with a homeless man on the steps outside the law firm. Inside the law firm’s hallway, the movie goes for low-hanging comedic fruit with riffs on a pimplenosed associate, a bad-hairdo receptionist (who knew she’s played by Cheri Oteri?), a coworker “not important enough to remember,” and an overweight colleague.

Even tiny parts get decent foils, including a tow-shop employee who takes advantage of Carrey’s vulnerability, a traffic cop who pulls Carrey over, and a jail guard giving Carrey his one phone call. When Carrey tries to dodge a trial by beating himself up, Fight Club-like, in a bathroom, it’s funnier because of the comedic foil who walks in and reacts.

The courtroom proceedings couldn’t be funny without a sense of structure and consequence, much of it provided by the grizzled, seen-it-all but patient manner of the judge, as played by Jason Bernard. Bernard is the best comic-foil of a judge in a courtroom comedy since Fred Gwynne in My Cousin Vinny. As the gold-digging and adulterous Jennifer Tilly’s boyfriend, Christopher Mayer goes from hunky boytoy to a flinching, cringing cross-examined witness as Carrey loses all composure and screams at him about his sexual trysts with her.

If you haven’t seen Liar Liar, check it out as the ultimate master-class in comedy foils. Even if you don’t like Jim Carrey, see it anyway. You can watch the entire movie with an eye on the actors whose work, as real people in a comedy, reacting and interacting, makes it possible for Carrey to be funny at a level he could never achieve as a lone comic.