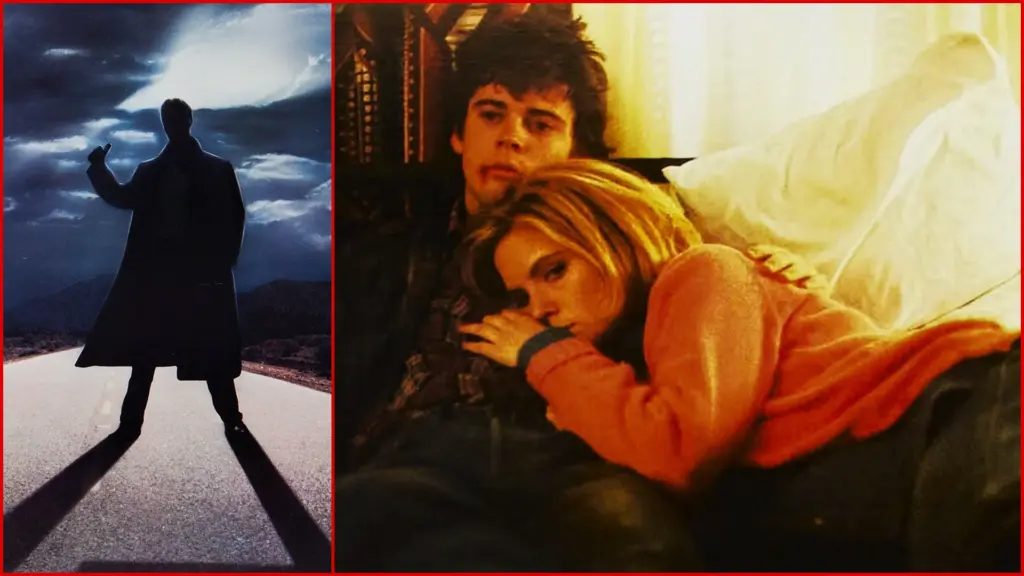

A rainy night. A lonely stretch of highway. Young Jim Halsey (C. Thomas Howell) is falling asleep at the wheel. After the white-knuckle terror of a near-collision, he pulls over to give a rain-drenched hitchhiker a ride.

“My mother told me never to do this.”

And so begins one of the most relentlessly terrifying and cruel horror films of all time. At its surface, Eric Red’s The Hitcher is a blistering, action-packed, serial-killer-on-the-road story, but there’s something more going on here. Something mythic.

The Hitcher is, if nothing else, a highly effective cautionary tale. Its moral is simple, listen to your mom! Don’t pick up hitchhikers. Just don’t. Ever. Because if you do, John Ryder (Rutger Hauer at his most predatory-sexy) is going to fuck you up.

When the film came out, critics and audiences were turned off by the lack of logic in John Ryder’s motivation and his seemingly magical ability to appear anywhere. To shoot up an entire police station like the Terminator and disappear without a trace. These arguments are far from invalid, but they seem to miss the point. The Hitcher isn’t about logic, it’s about death, specifically the death of youthful idealism.

And John Ryder is Death.

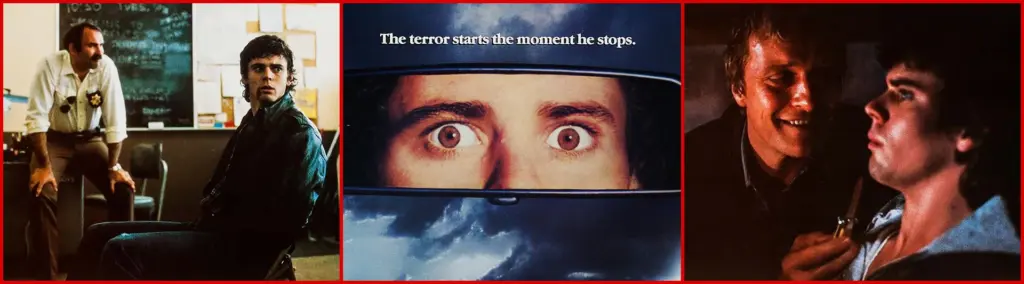

First off, this film is nothing without C. Thomas Howell’s stellar central performance as Jim. From the very first scene, he radiates a charisma and optimism that wins us over. We care about everything that happens because Howell makes up feel for this sweetly naïve kid. And we learn so much about him in his very first line “My mom told me to never do this.” We get that he’s a good boy and does indeed listen to his mom, most of the time. We also instantly understand that his emotional development is still lingering in a state of teenaged defiance. He’s not yet a man, but in a hurry to get there.

That’s when death first appears by the side of the road… and, blissfully unafraid of death, Jim invites him in. But fear sets in quickly as Ryder is creepy as fuck from the jump. Small talk turns sinister almost instantly and Jim, smartly decides that he made a mistake and that this ride is over. But instead of complying with Jim’s demand to exit, Ryder slams a switchblade to Jim’s crotch and demands he beg to die.

By this point in the 1980s I’d seen dozens of women threatened with sexual mutilation by murderous villains (the entire slasher subgenre is built on this motif), but this was the first time I’d ever seen such an attack on a young man. And I felt it. It was taboo and homoerotic and very real to me. It occurred to me that Jim Halsey was a Final Girl in male form, and he was up against a new kind of slasher. And like a final girl, he escaped using his brains and will to live. But that’s all in the first few minutes. That kind of scene is usually a slasher film’s climax.

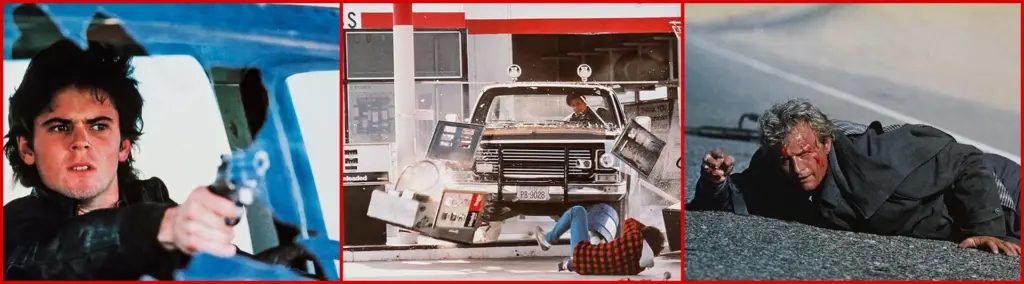

What follows is ninety minutes of non-stop death, destruction, and mounting terror as Ryder continues to kill and pins his crimes on young Jim. Because John Ryder isn’t just a vicious hitchhiking serial killer, and he isn’t just a slasher.

Like I said before, John Ryder is Death.

And the scene that illustrates this concept perfectly is the diner scene — not the finger in the french-fries (so gross), but the one where Ryder again mysteriously appears across the booth from Jim who, no longer naïvely optimistic, pulls a gun on Ryder and threatens to “blow his brains out his ass.” But Ryder spooks Jim, who pulls the trigger over and over; the gun is empty. Jim is broken, his hero-moment ruined, and he tearfully begs, “Why are you doing this to me?”

Ryder pulls the boy close and licks a pair of pennies before placing them on Jim’s eyes and says, “You’re a smart boy, figure it out.” And then slides him the bullets that he magically took from Jim’s gun. More than physical dominance, the action is clearly an allusion to the ancient Greek tradition in which coins are placed on the eyes of the dead to pay the Ferryman to take them across the river Styx to the underworld. In doing so, Ryder is telling Jim that Death has cast its steely gaze upon the young man, and will forever stalk him.

The lesson is… death always wins. Every time Jim thinks he can outwit Ryder, things get worse for him. And when Jim takes a liking to a local waitress (Jennifer Jason Leigh), Ryder decides to teach him this lesson in death the hardest possible way.

I won’t spoil the incredibly violent and bleak end to this character; it truly must be witnessed to be believed. In movies like this, a character like the waitress exists to be protected by the hero. In The Hitcher, the hero can’t win. No one beats death.

It isn’t until the film’s final moments that Jim sees Ryder for what he is. Jim no longer believes that the good are safe, that the authorities have any actual power, that justice exists, or that killing is absolutely wrong. All he knows is that he must kill to live. And in the final moments, Ryder gleefully accepts his fate, having effectively killed Jim’s innocence.

The Hitcher is a modern myth warning those who would defy death that, good or bad, old or young, death holds dominion over us all. If I ever meet Eric Red, I’ll thank him for my first lesson in nihilism.