Warning: This analysis of Burn After Reading is loaded with spoilers. If you haven’t seen the movie, we recommend you watch and enjoy it, free of mental baggage, and then come back and read this take on it. (Then, after reading, burn…)

I’m going to tell you a secret that apparently even a lot of Coen Brothers fans don’t know. At least I think it’s a secret. I kinda want to believe it’s a secret, because that would make the smart guy who figured it out and could take credit for figuring it out (is there a prize?). Which, in turn, would make me feel more conspiratorial satisfaction letting you in on the secret.

The secret, which I’ll tell you in a minute, has to do with Burn After Reading (2008). The film, an ensemble-based comedy set in Washington D.C., is one of the Coen Brothers’ in-between works: Not universally adored like Fargo (1996) or The Big Lebowski (1998), but not largely forgotten like The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001) or considered a misfire like The Ladykillers (2004).

When Burn After Reading was in theaters, it swooped in, made a strong profit, and disappeared without much extra hubbub. Unlike No Country for Old Men (2007) or O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000), Burn wasn’t an indie-movie darling, didn’t have the imprimatur that came with being a Cormac McCarthy adaptation, or an amazing soundtrack of bluegrass, gospel, and Southern folk music. Nor was it an award magnet like Fargo.

Instead, Burn After Reading left audiences amused, perplexed, and a little downbeat. This black comedy pulled no punches, killing off several of its most likeable characters, and was accepted as piffle. Like The Big Lebowski, Burn has a shaggy dog story; it teases you into thinking it’s going somewhere, and the ultimate laugh is the reveal that it isn’t.

The Big Lebowski ambled its way through its shaggy-dog story via absurdism, bowling dreams, electropop Nihilists, windy cremains, and the singular charm of The Dude; but Burn After Reading is relentlessly punishing. The New Yorker‘s David Denby reduced the story to “terminal misanthropy.” Time magazine critic Richard Corliss called the movie baffling, confessing that he “didn’t figure out what [the Coens] are attempting.”

So The Big Lebowski became the quote-memorized cult film (though I’m convinced 1987’s Raising Arizona is the best of all), revived again and again, commemorated with The Dude costumes and trivia contests, and who still watches Burn After Reading?

Well, I do. Which leads back to the secret, or at least I think it’s the secret: that Burn After Reading is one of the greatest Seven Deadly Sins movies ever made.

Not that there’s a lot of competition. I can think of only two really good ones:

First is Bedazzled, director Stanley Donen’s 1967 Dudley Moore and Peter Cook comedy about a man who make a Faustian bargain with the devil and gets seven wishes, each of them cleverly undermined, while the Seven Deadly Sins linger around the sidelines. In that wonderful, one-of-a-kind movie, cinema’s ultimate sexpot Raquel Welch shows up as Lust, or Lillian Lust to be exact, and….you just have to see Bedazzled. Please do. The updated 2000 version, directed by Harold Ramis and starring Brendan Fraser and Elizabeth Hurley, is cute too.

The other great Seven Deadly Sins movie is, of course, 1995’s Seven (or Se7en), the grotesque police procedural that was director David Fincher‘s calling card, and left many viewers haunted with echoes of the final scene’s “What’s in the box?” question. Oddly enough, both Seven and Burn After Reading feature Brad Pitt, making him the only movie star (that I’m aware of) to prominently appear as two of the Seven Deadly Sins.

Again, it’s remarkable how under-the-radar Burn After Reading‘s schema appears to be (perhaps it’s so obvious nobody bothers to mention it?). The movie’s Wikipedia page doesn’t mention “seven deadly sins” at all. When I’d search Google for “burn after reading” and “deadly sins” together, most of the hits were for websites that listed Brad Pitt movies and then referenced the plot of Seven. I figure there have to be people out there who’ve caught on to the “secret” about Burn After Reading, but the only Google search hit I ever found, years ago, was to a reviewer named Giovanni Fazio at The Japan Times who briefly mentioned the Sins in a Burn After Reading review, without going into details.

Anyway, it’s likely there are numerous cinephiles and cryptolo-film-ologists out there who also figured out the secret, and I know it’s not exactly an earth-shattering revelation, or a Stanley Kubrick-level enigma along the lines of The Shining and Room 237. But it’s a fun key to unlock the likely origin of the Coen Brothers’ writing approach. It compellingly answers the question “Why does this movie exist?,” making its character studies feel far less random and more focused. On repeated viewings I’ve found numerous clues that bolster the Seven Deadly Sins theory.

Before we go into details, here’s a refresher about The Seven Deadly Sins. These vices have been part of Christian theology and literature since the Middle Ages. Religious or not, they’re a well-narrowed grouping of foibles that indeed should be avoided by people trying to live their best lives.

The sins are: Anger/Wrath, Greed/Avarice, Lust, Vanity/Pride, Gluttony, Envy, and Sloth.

There are also Seven Capital Virtues: Chastity, Temperance, Charity, Diligence, Patience, Kindness, and Humility. It says something about our nature as humans that the Seven Deadly Sins get far more attention, in literature and the arts, than the Seven Capital Virtues do.

Okay, let’s get to the rundown of Burn After Reading characters and how they embody their respective sins:

Anger: Osbourne Cox (John Malkovich)

Burn After Reading starts at bland government offices where Osbourne, a CIA analyst, is being demoted, and within seconds Malkovich is yelling at everybody in the room. “This is a crucifixion!” he rants, revealing the temper that no doubt is why his career has imploded. (This opening-scene reference to crucifixion is also a hint to the story’s religious schema.)

Cox’s analyst expertise, mentioned in passing, was the Balkans — the basis for the word “balkanization,” which has to do with separating factions so they’ll fight each other…which is exactly the plot of Burn After Reading.

Soon it’s evident that Osbourne has a habit of drowning his rage in alcohol, as he runs off to a drunken party of Princeton Alum and sings with as much fervor as he yells.

Most of the rest of Burn After Reading involves other characters’ attempts to blackmail Osbourne over a data disk he lost. He screams at them on the phone, punches one in the face, and eventually boils over to all-out violence.

Osbourne’s other sins: Gluttony, due to his drinking. Sloth, due to his post-job aimlessness.

Greed: Katie Cox (Tilda Swinton)

Osbourne Cox’s wife, Katie, is among Burn After Reading‘s most underwritten main characters, but Tilda Swinton’s poise and presence (and flattering red hair, along with her oft-worn necklace of pearls) makes her a memorable figure in the story.

If Katie seems relatively unaffected by her husband’s bouts of rage, in large part that’s because of her own plans: To divorce him and take him for every penny. Which, with the help of an experienced lawyer (in one of two mansplain-ey scenes featuring offbeat older character actors), she does — exacerbating Osbourne’s anger in the process. Sins beget sins.

Katie’s other sins: Lust, in her affair with George Clooney’s character (her Greed kicks in there too, trying to secure Clooney as her next husband). Vanity, when she’s seen primping in a mirror. Anger, in her irritable handling of a kid at her pediatrician practice, or when she calls the Clooney character’s wife a “stuck-up bitch.”

Lust: Harry Pfarrer (George Clooney)

Burn After Reading is one of four Coen Brothers movies featuring Clooney — and one of three in which he plays a goofy idiot. Harry Pfarrer, though married, has an extensive sex life that not only includes steady, sex-pillow-augmented dalliances with Swinton’s character, but also involves an online romantic-match service that supplies him with one-night stands.

Eventually that links him to Frances McDormand’s character, who appreciates not only Harry the Sex Machine, but an actual sex machine that Harry has constructed in his basement. This guy has a real lust for being Lust.

Harry’s occupation as a U.S. Marshal helps the movie’s shaggy-dog misdirection by making it appear he’s being followed due to spy stuff, when in fact it turns out he’s getting out-Lusted by his clever wife (a potent side character played by Elizabeth Marvel).

Harry’s other sins: Gluttony, such as when he scarfs cheese in an early party scene. Vanity, revealed in his constant desire to “get a run in.”

Vanity: Linda Litzke (Frances McDormand)

It is little surprise that Frances McDormand plays the most pivotal of all the roles in Burn After Reading, given that the brilliant actress is director Joel Coen’s wife and most consistently valuable creative partner (outside of brother Ethan).

McDormand’s Linda character is a hilarious caricature of Vanity, who starts the movie having decided that several surgical cosmetic procedures are essential to her fulfillment. (The first we see of her is her “ham hock” arm in a prospective surgeon’s office mirror.) Linda’s peppy but determined obsession with these surgeries drives the main plotline of Burn After Reading, as well as driving most of the mayhem and violence. As the 1980s pop song by ABC says, Vanity kills. Or in her case, gets others killed.

By the end of the movie, as Linda is followed by government spooks and surveillance helicopters (in a paranoid scene reminiscent of the final act of GoodFellas), this embodiment of Vanity indeed has become the center of attention.

Linda’s other sins: Greed, not only through her extortion scheme but extended in her attempt to sell secrets to the Russian embassy. Lust, perhaps, given her positive response to Clooney’s sex contraption.

Gluttony: Chad Feldheimer (Brad Pitt)

I think the fact that the handsomest man in the world is playing Gluttony is part of the reason so few people link Burn After Reading to the Seven Deadly Sins. How can Brad Pitt, playing a personal trainer in top physical condition, be Gluttony? He’s the opposite of corpulent.

Look more closely, though, and you’ll see that Chad (Pitt) is eating, drinking, or chewing gum in nearly every scene. When Linda invites Chad to her apartment so he can call Osbourne to blackmail him, the first thing Chad does, after bicycling over, is raid her fridge. Burn After Reading is part of the reason there are memes about Pitt often snacking in his movies (or maybe that tendency further conceals his Gluttony symbolism in this film).

As funny and surprising as Pitt is, especially when he tries and fails to intimidate Malkovich by weirdly saying “Osbourne Cox” repeatedly, the fate of the Chad character is also the movie’s biggest shock. It’s as though all the Gluttony finally had a “wafer-thin mint” explosive result.

Chad’s other sins: Greed, by joining Linda’s attempt to extort money. Vanity, given his gleeful use of the gym’s exercise equipment.

Envy: Ted (Richard Jenkins)

In 2008, Richard Jenkins was in a fine indie film called The Visitor, which underscored his perfection at playing a lonely, despairing man. Which might be why the Coen Brothers chose him as Ted for Burn After Reading, too.

As the gym manager supervising Linda and Chad, Ted is so self-effacing that the script doesn’t bother giving him a last name. He’s often seen lurking on the sidelines, staring longingly in Linda’s direction. He clearly wishes Linda would hook up with him instead of the men she browses online.

Ted reminds me of every cuck-ish guy who ever got stuck in the orbit of a narcissist gal (yes, that happens in reverse) — a self-reinforcing, unrequited (dis-) connection. Anyway, Jenkins is great, though his Ted is most definitely not going to fare well in this story.

Ted’s other sins: Sloth, given his “leave me out of it” response to the discovery of the mysterious data disk. Also, Lust? Ted mentions (and has a pocket photo of) his previous occupation for 14 years (7 + 7) as an orthodox priest — which he had to leave under apparently shameful circumstances. His former priestly status serves as another hint to the fim’s religious theme.

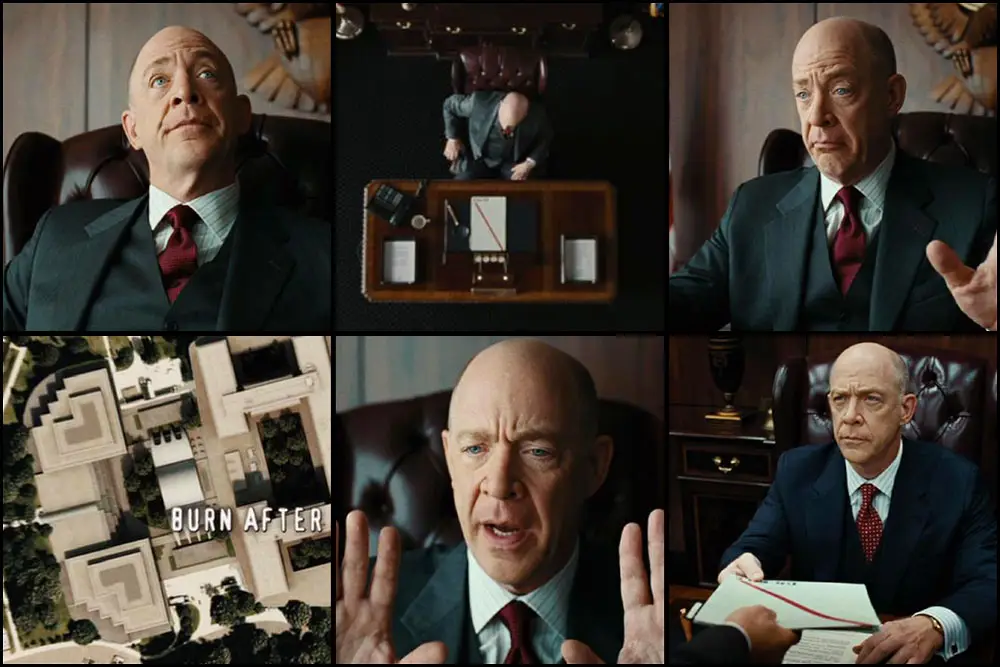

Sloth: The CIA Supervisor (J.K. Simmons)

This is another one out of left field, as J.K. Simmons‘s character is only seen twice in the movie, once toward the middle and once during the wrap-up. Simmons is the CIA Supervisor reported to by all the surveillance agents watching Anger, Greed, Lust, Vanity, Gluttony, and Envy destroy each other.

When he hears about Lust killing Gluttony, or Anger killing Envy, what does this CIA Sloth do? Nothing. He does nothing, nothing, and nothing. “Let’s wait and see,” he says.

What should be done about a body? “Hide it, get rid of it.”

Every situation or problem is met with the equivalent of “I don’t care, not my problem,” which, in this movie’s warped and deeply black humor, is how Sloth ended up at the top position in the CIA.

We don’t even ever see Sloth move: The other government agents walk down long hallways to get to him, always sitting at his desk. J.K. Simmons embodies his Slothy role with a humorously abrupt and flippant manner.

The CIA Director’s other sins: None, as they would require effort. He’s even too Slothful to find a point to it all: “What did we learn? Fuck if I know.”

More Sin-ful Symbolism

Once I realized what Burn After Reading was up to, I started seeing hints everywhere. Some had to be intentional on the part of the Coen Brothers, production designer Jess Gonchor, cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, and others on the film’s creative team. Some might be my own apophenia (hey, it’s harmless!). Here are some examples:

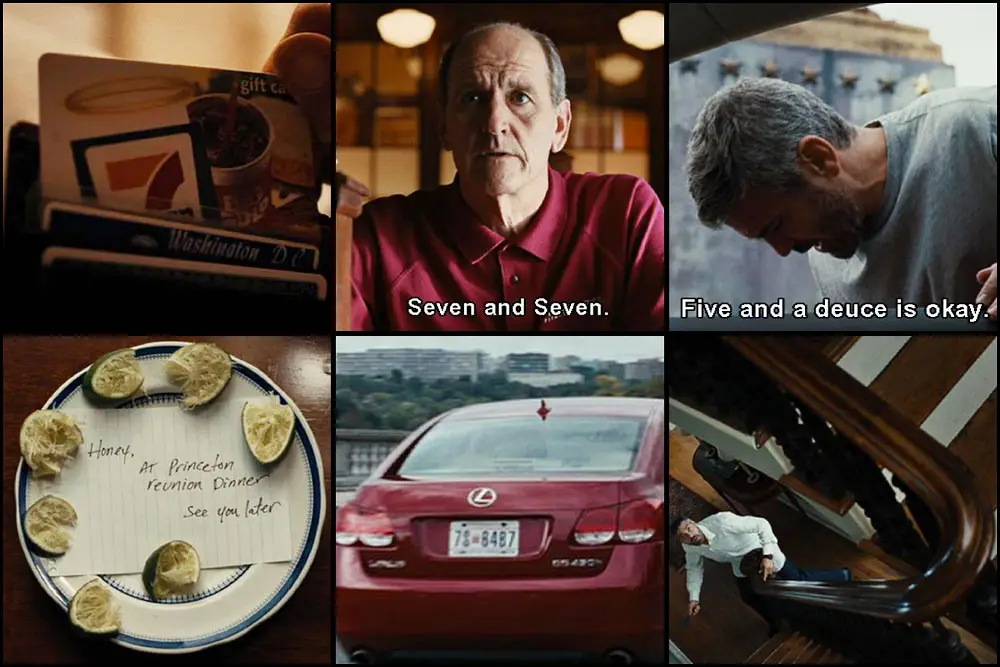

The gift card: The Seven Deadly Sins theme is hinted when Linda has a one-night stand (with a creepily blank-expressioned, insect-looking man) and searches his wallet to find out more about him. Before she discovers he’s married (adultery is a running theme in the movie), she pulls out a 7-11 gift card, revealing only the “7.”

The lime wedges: When we see a plate of limes that Osbourne has used while drinking alcohol, there are seven of ’em. Seven limes’ worth is a lot of drinks even for an alcoholic, but not if the filmmakers are dropping numerical hints.

Seven and Seven: Speaking of alcohol, when ol’ Ted (14 years as a priest, remember) is at a bar late in the movie, he specifically orders a “Seven and Seven,” which oddly enough are the bookends on a license plate seen elsewhere. Seven Deadly Sins and Seven Cardinal Virtues, you dig?

Numbers everywhere!: There seems to be even more of a numerical scheme to the movie: Osbourne’s “clearance level is 3” and at Princeton he sings “Three cheers for old Nassau!”; Katie’s lawyer tells her “forewarned is forearmed”; Linda’s doctor highlights “four different procedures”; a Family Feud-like game show is filled with numbers and possible foreshadowing … and so on.

But I’m not going to try to figure it all out unless the Coen Brothers personally give me an award. This is too much, right?

But Wait…. There’s Mirrors. And Circles. And Virtues.

Mirrors: Throughout Burn After Reading, characters are seen in mirrors: At the cosmetic surgeon, putting on makeup, seen in car side-view mirrors, or in house decorations. Not a big clue to the Seven Deadly Sins theme, other than, of course, Vanity. But it does add to the sense of spy-movie paranoia that fuels the plotline.

It also gives me an excuse to mention one of my favorite gags from 1967’s Bedazzled, a Seven Deadly Sins movie mentioned earlier in this article. That film’s version of Vanity was a man who had a full-sized “vanity mirror” (with the light bulbs around its perimeter) physically strapped to his body, so he could look at himself all the time. But he could never see where he was going, and was always tripping on things. (Fantastic movie — see it!)

The wagon-wheel shape: There’s one more visual element in Burn After Reading worth mentioning: A sectioned wheel-like shape with wedge partitions. It appears as a decoration in at least three places: Osbourne Cox’s basement, Osbourne’s boat, and a wallhanging in Linda’s kitchen. Might as well also mention the similarly shaped daisies in the movie poster for Burn After Reading‘s goofy, Sack Lunch-like, fake rom-com, Coming Up Daisies.

This repeted shape bears a strong resemblance to classic images of the Seven Deadly Sins, particularly one by noted religious painter Hieronymus Bosch.

The Seven Cardinal Virtues: Having taken all of these details and non-coincidences too far, here’s a final indulgence: What if the characters in Burn After Reading also represent the Seven Cardinal Virtues?

Ted, once a priest, must have known something about Chastity, and the first time he’s at the bar he shows Temperance by ordering only a Tab. Ted also demonstrates the virtue of Humility when he talks about his background.

Harry shows Temperance by saving money building his sex machine from scratch, and also Diligence in his creation, as well as in his exercise habit.

Osbourne shows Temperance by waiting till 5 p.m. to drink, and carefully pouring some of the liquor back into the bottle.

Katie Cox shows Temperance by waiting a day before initiating her divorce, and she has “patients” (Patience) at her doctor’s office.

Certainly Chad shows the virtue of Kindness when he continually helps Linda attempt to fund her surgeries; and Katie shows Kindness driving Harry 5.2 miles so he can “get a run in.”

At the end of the movie, the CIA Director demonstrates Charity by granting Linda the money for her surgeries.

And with that, this theory has become too much. Gluttonous, perhaps. If you ever share it with other Coen Brothers fans, be sure to give credit where due, as my own Vanity demands.