There’s a quote from a Deadline interview with late director Jonathan Demme in 2016 where he’s talking about reading The Silence of the Lambs and feeling like, “This could be the scariest movie ever, and I wanted to make that movie. I wanted to make a Psycho-caliber fucking terrifying movie.” Flash forward to 2024 where things have come full circle, and the Psycho star Anthony Perkins’s son, Osgood Perkins, is now releasing his new film Longlegs, a grappling feat of filmmaking which viewers have called a modern-day Silence of the Lambs.

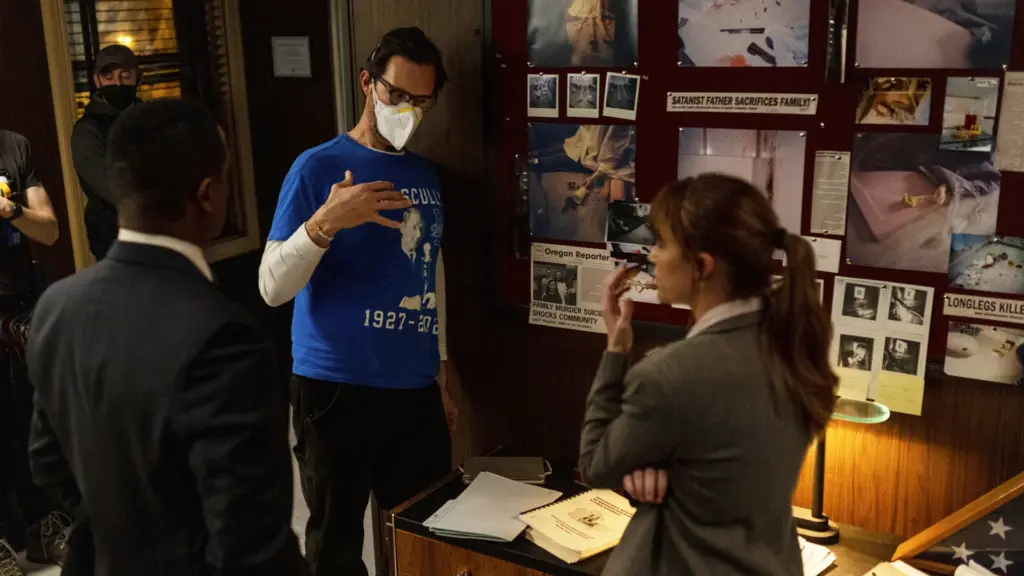

In director Perkins’s latest entry, an FBI agent uncovers a series of occult clues all leading her to a notorious serial killer who goes by the name of ‘Longlegs.’ Starring Nicolas Cage in a terrifying turn as the man downstairs himself, and Maika Monroe as the agent hunting him down, this surreal foray into a living, breathing nightmare is already being heralded as one of the scariest movies ever.

Unsettling trailers aside, indie studio Neon has demonstrated how proper marketing can create a sense of pre-viewing dread for an audience. Billboards featuring cropped photos of bloody crime scenes and stark red cryptic messaging line the streets of Los Angeles, and myriad plastered posters offer a creepy phone number to call and listen to a message left by the fictional serial killer. The Seattle Times even published Longlegs’s code in their paper, which hardcore fans are deciphering online. The movie is firing on all cylinders before it’s even gone for a ride.

I was fortunate enough to sit down and talk with writer/director Perkins himself ahead of the release of his latest picture on behalf of Screenopolis. [Fair warning: This interview contains spoilers! Spoiler-free: Our Longlegs review. —Screenopolis Department of Non-Spoilering]

We discuss crafting the look of Longlegs with renowned makeup effects artist Harlow MacFarlane, working with the legend Nicolas Cage, the inspiration behind the infamous algorithm, the impact that becoming a father has had on his filmmaking, our shared love of Michael Mann’s Manhunter, and why the director feels that the real key to making movies lies in the steadfast routine of writing every single day.

Kalyn Corrigan: A lot of people have been comparing Longlegs to The Silence of the Lambs, and rightfully so. It’s got that eerie, atmospheric, ‘90s feel to it. However, after seeing your film, I definitely get the Thomas Harris vibes, but as a big nerd who’s read all four of the Dr. Lecter books, I see Maika Monroe’s Harker as more of a female Will Graham than a Clarice Starling. Can you tell me about Harker’s heightened intuition and the decision to connect her to Cage’s serial killer Longlegs?

Osgood Perkins: I think you’re right to say that she’s more like Graham. I always really took a shine to those scenes in Red Dragon and Manhunter when he goes to the house, and he communes with the energy of the thing, and you see that he really feels the events that took place in the house. To me, that’s the scariest part of Michael Mann’s Manhunter, when he goes back to the house and he’s there in the dark. That’s great stuff. Yeah. I mean, the idea was to really just, I don’t want to say rip off Silence of the Lambs, but to revere and to honor it. In the same way that Warhol honored the Campbell’s soup can, and said, you know this thing from your everyday life, and now we’re going to repurpose it, and we’re going to use it differently. That was the intention going in with it, and I had all of the the good serial killer movies – and there are not very many of them, there’s a few – I had all of the good ones dancing around in my consciousness, in my psyche, and letting the best elements of them come forward and then be reshaped. It’s really hard to describe and discuss and to quantify the creative process, because it’s just doing it. It’s sitting down every day, and writing a lot of words and hoping that something takes shape out of all that stuff.

What about Longlegs’s algorithm? Where did the inspiration come from for that type of coding, and when did you decide to carry it over into marketing?

The algorithm was something that I and one of my producers, his name is Dan Kagan, that we – there was a time in pre-production, as you’re gearing up to make the movie, when you’re refining everything. You’re making sure everything fits, you’re making sure you have it all, you’re making sure the script works, you’re making sure the locations are blah blah blah blah – everything is being planned. Dan was rightfully focused on the fact that we really needed those kinds of breadcrumb elements, right? We really needed to engage the audience in the oh, oh, oh, oh thing. I didn’t have maybe enough of those in the script as I had written it. So, Dan and I put our heads together on quite a few long nights of just batting it around and trying to find the thing that would be visual. Trying to find the thing that would ultimately be simplistically visual, which is the upside, the inverted triangle – kind of how water goes down a drain, right? It has that funneling effect. We got onto that riff and then we just figured it out. You just sit around long enough talking about it, and banging your head against it, and writing a bunch of words and you hope that somewhere in there it kind of trickles out.

How did Longlegs’s love of the devil impact the way that you and makeup effects artist, Harlow MacFarlane, brought the character to life?

The idea as written in the script was that he has his career as a sort of henchman of the devil, right? Like an agent of Satan, let’s say. His life, his career as that had left him pretty fucked up, right? It left him pretty demolished, pretty ruined, pretty wrecked. Like someone who’s been a fentanyl addict for a few years, it really twists your whole everything. So, the idea was that we were gonna meet this guy, and he was gonna be really ruined from the inside out. And that bad plastic surgery was gonna be something that he tried to change himself, to hide his true self to make himself look better, to make himself feel better as an outward manifestation of how rotten he felt on the inside. Just the very simple supposition that if you’re the mouthpiece of the devil, or if you’re one of the devil’s hands, it’s not so great. It doesn’t build you up, it takes you apart.

How did you play with the aspect ratio to affect the atmosphere? There’s a moment in particular that stands out to me, where Harker is alone in the middle of the frame and you narrow the aspect ratio and it looks like the walls are closing in on her and it creates this very claustrophobic effect.

Well, we used the 2.39:1 for the present, the ‘90s, and we used the 4:3 for the sort of memory in the ‘70s. Then, when those two things started to interact with each other, we have Harker wake up into a 4:3 frame. She basically wakes, it’s almost like waking up out of memory, and then emerging out of that back into her real everyday present day life. So actually, the aspect ratio stretches from 4:3 back into 2.39:1 as she comes back into her normal reality from the square, from the containment of memory, she comes back out into the regular reality.

You’ve said that this movie is about “the power we have over our children to shape their perception of things.” What did you mean by that?

Just that as a parent, you become aware that you are the primary formative agent for your children. Your children are going to get most of their cues on how to interact with the world, how to interact with their own emotional states, their thoughts and feelings – they’re gonna learn how to do that through you. There’s a tremendous amount of power in that, which can be well handled or abused. If you think of a movie like Dogtooth, right? Which is like the most extreme example of parents just fucking with kids’ perceptions for their own purposes. But the idea just being that parents sometimes have to craft protective narratives around certain things, and that situation in Longlegs is taking it to a really sort of baroque extreme. It’s kind of the worst possible version of that, the worst possible version of a cover story. Just when there’s things in a child’s life, or a family life that you don’t need them to know, or want them to know, you go to a certain length to protect that, and often that looks like making a fiction around it. Longlegs is really just a movie about a mom making it so that her kid doesn’t know what’s really happening.

There’s been a lot of praise about Maika Monroe and Cage’s performances in the film, and for good reason, but even from The Blackcoat’s Daughter, you were always getting strong performances. How has your method of working with actors changed over time?

I think it really comes down to being more confident as a writer and then casting the right person. Once I’ve written the words properly, and by writing the words properly, I mean, once I’ve written things for people to say that suggest what they feel, and what they mean, suggest what’s really going on for them, suggest a rich subtext, but don’t say that subtext. Actors really gravitate towards that kind of writing. Actors don’t want to play commentary, right? They want to play the oppositional force around not saying exactly what you mean. So, in practicing that, and trying to get better at that. Then, as you go through your career, you get access to better actors – and by better actors, I mean people who can pour themselves into the text more completely. I’ve found that the actors that I’ve worked with, especially Nicolas Cage in this case, Maika Monroe, also, but Nicolas Cage surprised me in how faithful he is to the product, and to the project, and to the vision that is the director’s. He’s not there to serve Nicolas Cage, he’s there to serve the vision, to serve the movie as it is, and to serve the text as written. So, if the text is there, and you’ve got actors who really want to explore it, it can work out pretty well.

What did working on this project teach you?

Probably just, the great currency in art, I suppose, is confidence. Especially in the art of directing a movie, the confidence in your decisions, the confidence in your taste, confidence in what you think is right, what you think is good. Because at the end of the day, my job really becomes choosing this, but not that. Especially from the blank page, right? You gotta make a choice every day, every sentence. You gotta, it’s this, but it’s not this. The more you do it, and the more you show up, and the more you stay honest, and write about what you know, that is to say, write about your own personal truths and personal experiences. When you use that as a way to cut through the bullshit and a way to give yourself a mooring or an anchor or a center, and you just keep at it. At a certain point, you find that you get good at it, like anything that requires practice. I think if I can encourage anybody out there trying this, it’s just that you gotta practice a lot. You gotta show up every day and do it. You gotta show up every day and type words. Showing up every day and thinking about it is not, that doesn’t count, right? Thinking about writing and writing don’t have anything to do with each other. You gotta start putting words down, and do as much of it as you can all the time. Just practice.