Jason Yu, a visionary filmmaker who came up under the wing of cinematic juggernauts like Parasite helmer Bong Joon-ho and Lee Chang-dong of Burning fame, has entered the chat.

After learning from the masters, Yu set out to make his own film, Sleep, a directorial debut that earned him the Grand Bell Award in South Korea, the Discovery Award at the Raindance Film Festival, Best Screenplay at the Baek Sang Art Awards, Best Actress at the Blue Dragon Awards, and nominations at Sitges and the Cannes Film Festival.

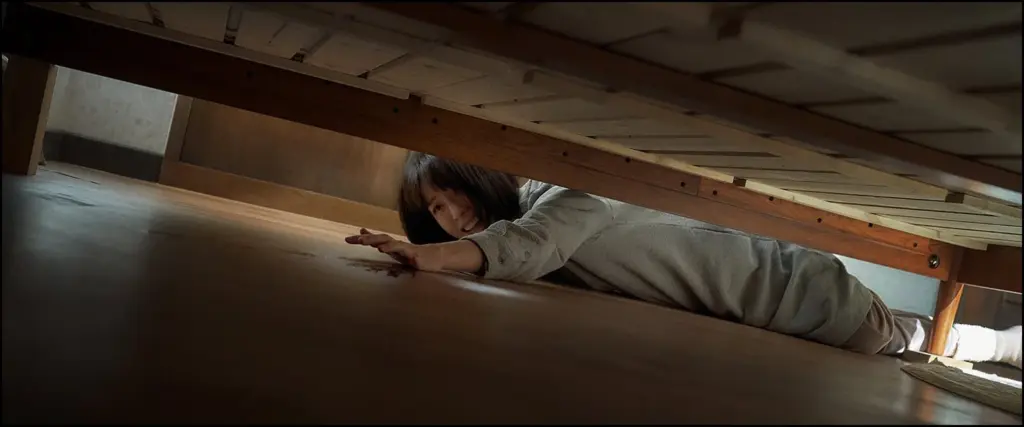

In the film, an expectant couple finds their happy marriage upended when the man of the house, Hyun-su (Lee Sun-kyun) begins experiencing strange disturbances in his sleep. Awakening randomly one evening, Soo-jin (Jung Yu-mi) finds her loving husband sitting at the foot of the bed they share, seemingly staring at nothing. “Someone’s inside,” he says to no one in particular.

From that night on, whenever he falls asleep, Hyun-su exhibits increasing erratic compulsions, as if transforming into another person in his nocturnal state. Overwhelmed with anxiety that he may hurt himself or their young family, Soo-jin grows increasingly afraid of her partner. Despite treatment, Hyun-su’s sleepwalking only intensifies, and Soo-jin begins to fear that her unborn child may be in danger.

I caught up with writer/director Yu ahead of the film’s release, and he spoke excitedly about how it felt getting the chance to be behind the camera for his thrilling new exercise in tension, Sleep.

During our chat, we discuss moving the camera to mimic the couple’s emotional states, learning from filmmaking legends, sparking a debate about ancient spirituality versus modern medicine and how the movie plays on the idea that you never really know who’s sleeping next to you.

Kalyn Corrigan: This film is unlike anything I’ve ever seen before. What inspired you to tell such a unique story, especially given that it’s your directorial debut?

Jason Yu: Thank you so much. It really depends on which aspect you’re talking about. If you’re asking about the inspiration for creating a horror film on sleepwalking, I think there are a couple. I guess the first one would be myself. I have a lot of bad sleeping habits and a severe case of sleep apnea. There are some times when I sleep that I forget to breathe, which is funny, because not breathing doesn’t really cause any sounds, but my wife, who sleeps next to me, seems to always know when that happens, and she wakes up because of it. She has to wait for me to continue to breathe for her to feel relieved. Even when I do return to normal breathing, just having witnessed the husband not being able to breathe, I think it shocks her into waking her up, so she’s no longer able to sleep all night. I only hear about it in the mornings, about how she’s sleep deprived because I was unable to breathe during sleeping. I was very sorry, and as guilty I felt about that, I was very fascinated about it because it’s just me not breathing. I’m not harming anybody. It’s just me, almost self-inflicting harm, but that created so much horror in her, that she was unable to sleep. I thought that there was something there.

I guess my imagination went to the next gradual step, which was, what would happen if my sleeping habits were even more severe? What if the symptoms were more grotesque? Eventually, what if I was harmed? What would happen then? I think that sort of scenario fascinated me into thinking about sleepwalking as a potential horror film. The shocking stories that you hear about sleepwalking, whether from the internet or documentaries, about somebody jumping off a building while they’re sleeping, driving while they’re sleeping or even harming someone.

I remember feeling an incredible shock about those stories. I wondered what the everyday lives of these patients might look like, but more importantly, what the lives of their loved ones, the ones who have to be around them, might look like. I thought that would also be an interesting story to tell. Most importantly, I created a horror film about a sleepwalking husband who terrifies his wife. But at that time, I thought it was very gimmicky. One night, it’s just the husband doing this strange, scary thing, and the wife is terrified. The next night, he does something even scarier. The wife is even more scared. I thought it was just this repetition of this gimmick, but I realized it could be much more. When I infused my personal life into the story, I began to gain more passion for it, and more inspiration for the project. At the time, I was preparing to marry my long-time girlfriend and I think, unbeknownst to me, this relationship, consciously and subconsciously, melted into the story. I think that’s why I made the protagonist a married couple, and revolved the story heavily around their relationship. That nugget inspired me and drove me to create this film.

At first, Hyun-su appears to simply be harmlessly sleepwalking and talking in his sleep, but then his actions turn more sinister, and it’s hard to tell if Soo-jin’s husband is entirely innocent. How does this movie play on the idea that we never really know who we’re sleeping next to?

I think that’s almost the biggest thing. The act of sleep is such a … how should i say it in English? Sleep is such a merciless state. Do you say merciless? You’re at the wheel of your surroundings. It’s a very trusting thing, sleep. It’s very peculiar in that you lose consciousness. You have to have absolute faith that you’ll be safe while you’re sleeping, and that the person next to you will be there to protect you. I really liked that aspect. I really liked spinning that aspect of sleep. What if the person you trust the most while you’re sleeping is the person who’s the biggest threat to you, when you’re in this merciless or this vulnerable state? I thought that would be the biggest fear mechanics going into the film.

The way you position the camera seems to really immerse the viewer in the tension that the couple is feeling. What kind of camerawork are you using to convey the psychological states of Hyun-su and Soo-jin?

I think the rule of thumb between me and my cinematographer was that we wanted to follow the psychology of the wife character as much as we could, especially in the first half of the film. Any way to capture the shift in emotions, or the site, or how she’s feeling, or the shift in their relationship, that was the priority in cinematography. Being a single location film, and that location being such a bland box of the room, we didn’t really have much cinematic advantage for the background. So, we really honed in on the actors, and their performances and their relationship. I think because of that, we were able to really capture the gradual changes that happened in the wife’s character and their relationship.

Actually the cinematography differs from chapter to chapter. For example, in the first chapter, we really wanted to emphasize the love and the coziness that they feel around each other, the trust and their bond, so we shot it in a way that would enhance that. For example, most of the shots are them together, ongoing lengthy two shots that would really emphasize that aspect. In the second chapter, where you wanted to make the protagonist feel like she was trapped almost in a jail cell, we made it so that there were a lot of claustrophobic single shots with the production design, making the house feel like a jail.

After running out of scientific options, the couple begins to wonder if maybe Soo-jin’s mother is right, and they actually need a Shaman. How do you use the vehicle of this tumultuous story to spark a debate about ancient spirituality versus modern medicine?

Oh, that’s very interesting. The protagonist resorting to shamanism, I think it effectively shows how far she’s come, or the descent of her psyche at that time. She kind of blew a sneeze at it at the beginning, right? And in the end, that’s her last resort. But as for shamanism and medical science, it wasn’t really much of a commentary on that. In Korea, I think shamanism and medical science both have deep roots, and they somehow find a way to coexist in our society. If this same thing happened in a Korean household, I think they would have pretty much gone the same way. First, they tried to find a medical reason for it, and when those things fail, it’s not an unnatural progression for them to resort to shamanism like that.

It’s interesting, because I think in Korea, if you have 10 Korean people in a room, at least one or two have visited a shaman, and they have those tokens in their wallets to bring them good luck, good ghosts, or to fend off bad ones. Although these are very contradicting things, I think it’s just our culture. It feels quite natural that they gel and exist together. So, I thought it was just a natural progression to the story, and what would be the natural thing that these characters would do in a Korean society.

You’ve worked with such cinematic titans as Bong Joon Ho and Lee Chang-dong. I mean, what lessons would you say that you took from these experiences that you brought with you while making your first film?

Two different things. I think everything I learned about filmmaking at least, I learned from Bong Joon Ho, because I never went to film school. My film school, I think, was working as an assistant director on the project Okja for two and a half years. I was able to observe how we directed for each stage of production, from pre-production to post-production, and even promotion. At the time, I didn’t really think I was learning anything. I was just trying to pull my own weight and not ruin the film. But when I was creating Sleep, I realized I was trying to consciously make out who was doing every step. That’s when I realized, ‘Oh, I did learn everything about filmmaking from this guy’.

To be specific, the biggest one would be just drawing every single storyboard yourself, and adhering to the storyboards during the shoot. Having this great faith in preparing the storyboards and trying to shoot what you prepared. Although Director Bong does deviate, and he does have these improvisational changes on the spot. Like him, I do try to adhere to what I prepared and then be accepting of the things that I cannot contain or predict.

For Lee Chang-dong, I only worked with him in a small way. I created the English subtitles for his film, Burning, for a month or so. But I did really learn a lot from that as well, because I was very shocked to find out that although he’s not an English speaker, he was very meticulous about every sentence, every word that I used. He needed a purpose. He wanted to know my purpose of why I translated it in a certain way, and not another way. I realized how even if it’s not your field, not being an English speaker, you have to know the intention of everything, of all the elements within your film. I was very impressed by how meticulous he was, and even in the smallest way, and I really tried to mimic that in Sleep.