Few screenwriters, living or dead, have achieved the status of household name.

Charlie Kaufman, the maverick behind some of the millennium’s most memorable films, is one of those few. While he has since directed three features, Kaufman’s directorial debut would not come until he had established himself as one of America’s preeminent penmen for the screen. Though, like his characters, I’m unsure he enjoys the distinction.

It is more than Kaufman’s unerring sense for the abstract and absurd that has left such an enduring imprint. Over a 30-year career he has dedicated himself, whether by virtue or ghastly ordination, to the investigation of the mind.

After slumming it for years in low-rent TV, with 1999’s Being John Malkovich (directed by Spike Jonze), first-timer Kaufman garnered himself an Oscar nom and produced one of the most enduring pop-cultural artifacts of its time. Following 2001’s Human Nature (directed by Michel Gondry), he went on to pen 2002’s Adaptation (Jonze again), the mutant work of metafiction for which Kaufman became the first and only individual to receive two Academy Award nominations for the same picture in the same category (the other nom going to Donald Kaufman, his fictional brother and co-writer). In 2004 came Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Gondry again), a pillar of the era for which Kaufman finally won the Oscar, alongside nonfictional co-writers Michelle Gondry and Pierre Bismuth.

In 2008 Kaufman made his leap to directing with the labyrinthine achievement Synecdoche, New York, after Jonze dropped out due to scheduling conflicts. Kaufman has since remained in the director’s chair, with 2015’s Anomalisa and 2020’s I’m Thinking of Ending Things, through which he has continued to chart, with whimsy and horror, the human interior.

The American Cinematheque recently ran a retrospective on Kaufman in Los Angeles, at which he appeared in person. I was fortunate to catch both Malkovich and Eternal Sunshine, and their ensuing Q&As, at the Egyptian Theater in Hollywood.

Malkovich and Sunshine: Dissimilar Greats

I had seen neither film in more than 10 years. Eternal Sunshine I saw upon its release, whereas I was a few years too young to have caught Malkovich in the theater. Watching them back-to-back I was struck by how dissimilar they are, despite overlapping in subject. Both films depict a cognitive process. Both films tell stories of guarded, powerless people seeking agency. Yet these shared themes trend in nearly opposite directions.

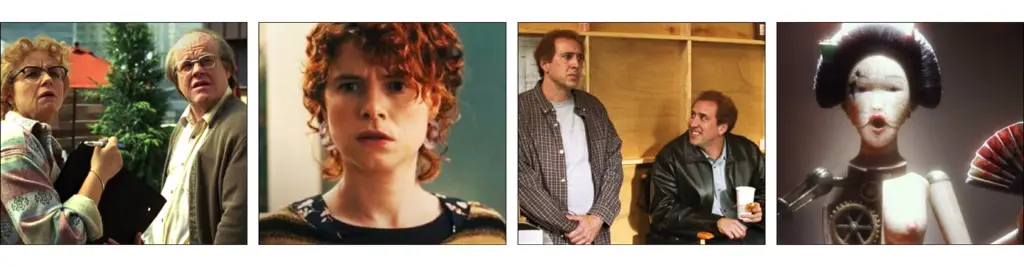

Being John Malkovich stars John Cusack as Craig Schwartz, an out of work puppeteer living in New York with his wife Lotte (Cameron Diaz), and her menagerie of exotic pets. Craig spends his days performing lewd, high-concept puppetry on street corners, and sulking in their apartment over his lack of artistic recognition. It is difficult not to see a self-deprecating analogue to Kaufman here, as can be found in much of his work. The highfalutin auteur, plagued by neuroses, desperate for the adoration of a rotten institution which spurns him.

When cajoled to look for work by a naively supportive Lotte, Craig finds a listing in the classifieds for a file clerk position at a local office building, which he is unusually qualified for given his deft puppeteer’s hands. Kaufman often enjoys the use of dream logic, and this fact, like many others, we must take in stride.

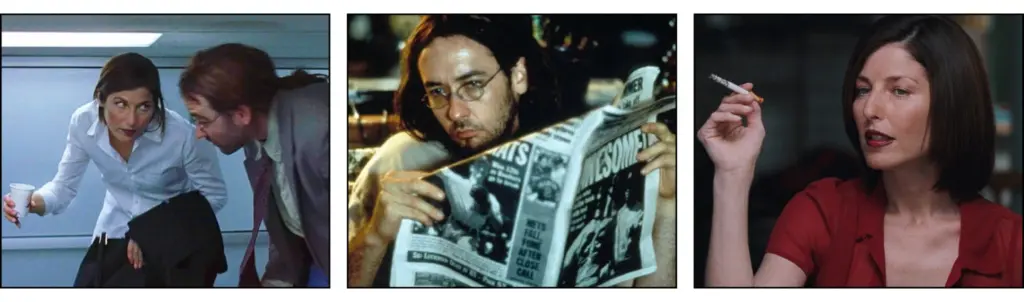

Craig is quickly hired on the low-ceilinged, seventh-and-a-half floor – and just as quickly falls in love with his imperious coworker Maxine, played by Catherine Keener. His affection is not reciprocated.

The opinions of others toward Craig often feel like those in a dream. He is isolated in an alien world, pathetic in his own right, yet judged and misunderstood by everyone around him. Quite literally misunderstood by his boss’s secretary, who is so hard of hearing she has convinced their employer it is he, in fact, who has a speech impediment. Malkovich is littered with these feelings of inner claustrophobia, and powerlessness, however comical.

Craig’s humdrum existence is upended when he drops some papers behind a large filing cabinet at the office. Pulling the cabinet away from the wall, he discovers a small door. Overcome with curiosity, he crawls through, only to be sucked through a portal into the mind of actor John Malkovich. After 15 minutes, Craig falls from midair covered in grease onto the shoulder of the New Jersey Turnpike.

Accepting this at face value, Craig sees an opportunity to garner the attention of Maxine and shows her his discovery. They decide to open the portal to the public at night and charge $200 a pop.

Craig reveals the existence of the portal to Lotte, and when Lotte meets Maxine she is equally smitten. Lotte and Maxine fall in love, but with a caveat: Maxine will only sleep with Lotte when she is in the body of Malkovich.

What ensues is a bizarre love triangle (quadrangle, if we count Malkovich); a struggle over power, fame, identity, gender and mortality. Craig’s puppetry takes on new meaning. Twists and turns abound, grander lore is inserted, all the funnier for its attempts to explain. A pattern of Kaufman’s, most prominent here and in Adaptation, is the blithe acceptance of a third act. The movie kicks into incongruous gear, as if to ask the audience, “Is this what you want? Is this what you paid for?”

Yet the central forces remain the characters, their journeys toward self-discovery, their small triumphs, their defeats. It is deeply funny, deeply human, totally strange.

My younger memories of the film were of something dark, disturbing; and it is that. But the crowded theater roared with laughter from start to finish. On my first re-watch in many years, I found it incomparable.

It is just as unbelievable today as in 1999 that Malkovich ever got made. And by first-timers, at that. Though Jonze was by this time a music-video veteran, having directed for Beastie Boys, Weezer, Dinosaur Jr., Bjork, Sonic Youth and many more, Malkovich was his feature debut. According to Kaufman, not only was this his first produced screenplay, but his first screenplay written.

Q&A: Charlie Kaufman and Catherine Keener

Kaufman was joined at the Q&A by Catherine Keener. When asked what he had expected of the project, Kaufman replied, “No, I didn’t think it was gonna get made… No one knew who I was. I was trying to write a sample. But I was also trying to write something that I felt was good. So, I wasn’t going to try to follow a formula or anything. These ideas seemed good to me. I got a lot of positive reaction from the script, but everybody said it would never be made. And that seemed to be the truth for quite a while, until somehow it fell into Spike’s hands.”

Kaufman clarified that John Malkovich was the only actor the role was ever written for. He said of his choice (to much laughter), “I mean, I really like John Malkovich’s name. I’ll preface it by saying that. But there is an oddness to him. And I think there’s kind of something in his eyes that makes him unknowable. So, I could imagine there might be somebody looking out. I didn’t, I couldn’t, think of anyone else. And yes, the name was very important. The name is funny.”

He described his bizarre first contact with Malkovich’s representatives years before, and how the film ultimately came together.

“I wrote the script, and it got to John Malkovich somehow. I got a call from his business partners, who wanted to meet. They were very interested in talking to me.” One of Malkovich’s business partners asked, “‘Why the seven-and-a-half floor?’ And I said, I don’t know, I thought it was a funny idea to have a half floor. And he said, ‘Did you know that John’s address is seven-and-a-half?’ I did not know that. And he didn’t believe me. It was clear they were basically checking me out.”

“And then some years passed, and Spike got involved. He went to meet with Malkovich; Malkovich really liked it, [but Malkovich] didn’t want it to be about him; he didn’t want to play the credit part. He thought it could be about somebody else. Either way, if it was a disaster or a success, he was afraid it was going to ruin his career. And I could understand that concern. But eventually he met with me and Spike together, and he decided he trusted us. And once he was in, he was in. ‘Make him more of an asshole,’ he would say. ‘Make him more ridiculous.’ He was great. He was really great. I certainly owe my career to him.”

Catherine Keener: “I don’t think anybody understood [the script]. So I read it. And I thought, ‘This is amazing. Who’s Charlie Kaufman? What’s the matter with you?’ But I just thought it was so new and fun. And it really warranted a lot of openness, which is always what you want to get into. And I just felt so lucky to get this job.”

When asked about their creative liberty during production, Kaufman explained, “It didn’t cost a lot. And it kind of fell through the cracks. The company that was producing it fell under; It got acquired by another company while we were making it. So nobody was, you know, minding the store. Nobody watched it at the studio, so it just… was fortuitous.”

Kaufman also described the original screenplay as having a markedly different third act. He explained, to more laughter, “The devil is in it, and puppets, and the world is destroyed, and the world is painted gray, and Lotte marries Elijah the chimp. And I like that ending.”

Revisiting Eternal Sunshine and Its Legacy

The Q&A ended, we raced outside to find our spot in the reentry line, and settled in for Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

Eternal Sunshine has an odd legacy. Beloved upon its release, it since has been unfairly sidelined with less-favorable examples from that period. Just old enough to be cringe, not yet old enough to be retro. If, as some do, you now group Eternal Sunshine with other mid-aughts indie darlings that have not withstood the test of time, you are doing it a great disservice.

Eternal Sunshine is every bit as outré and ambitious a picture as Malkovich (and nearly as funny), and brings with it a rare heart.

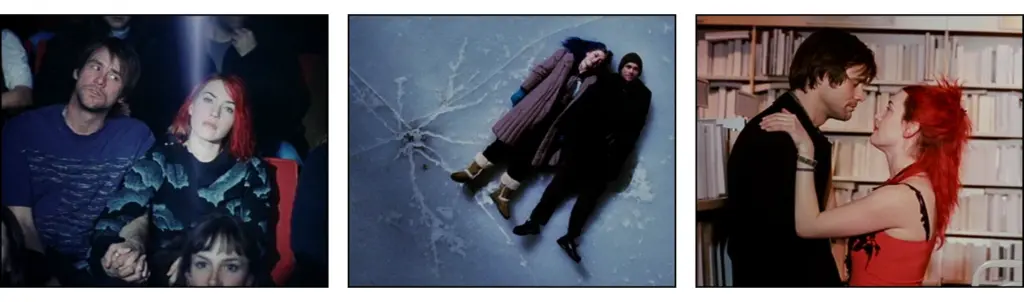

It follows Jim Carrey as Joel Barish, a mid-thirties introvert living in New York. The film’s timeline is fractured, but after a long and tumultuous relationship with Clementine (Kate Winslet), Joel discovers that Clementine has used an experimental service administered by the Lacuna firm to have all her memories of him erased. Distraught and disbelieving, Joel decides to undergo the same procedure in retaliation.

We watch as Lacuna’s technicians sift through Joel’s memories one by one, attempting to delete all evidence of Clementine. Joel both participates in, and annotates, these fragments of his ruined relationship.

The simple genius of the premise is that we are presented with a relationship in reverse. At the outset, Joel and Clementine are in their death throes as a couple. We hear Joel’s entrance interview with Lacuna as narration, and his remarks about Clementine’s character are ruinous. All the boredom and bitterness of a thing that has run its course.

After the brutal portrait of a breakup, earlier memories come to the fore and we see the moments between Joel and Clementine that stood as landmarks, and shaped the mythology of their time together. As the memories become sweeter, Joel realizes he wants out of the procedure.

Thus begins a wild chase through Joel’s psyche as he shepherds a shadow of Clementine through his innermost memories. Hopping between Joel’s mind and the Lacuna technicians on the outside, we meet a host of memorable side characters played by the likes of the late Tom Wilkinson, Kirsten Dunst, Mark Ruffalo, Elijah Wood, Jane Adams, David Cross and more. The central two performances are both career highlights, if not bests; and this supporting cast is instrumental in crafting the whole. Passing moments are imbued with wit and meaning. Past and present both are given life by their presence. I will never forget David Cross’s “Carrie, I am building a birdhouse!”

Q&A: Charlie Kaufman on Eternal Sunshine

While the story of Joel and Clementine may not feel singular, the way in which it is told does. Of the project’s genesis, Kaufman said, “Pierre Bismuth is a friend of Michel’s, and he’s a Belgian conceptual artist. And he had an idea for an art piece that was sending postcards to people saying that they’d been forgotten.”

The disjointed timeline works expertly, and is a large part of what makes the film so memorable. Further viewings are rewarded with a host of small details.

Of his writing process, Kaufman remarked, “I don’t think I go down blind alleys. I go down alleys, and then discover something, and then maybe go back to earlier points to insert something. So the thing I’ve discovered is set up.”

Gondry lends his unique eye to the affair. His natural quirkiness is muted just enough to tell the story, and his dream-sense adds an uneasiness to the film’s humor. Gondry’s signature visual effects are on great display, and quite striking. A few images in particular have really stuck with me over the years. A house crumbling on a winter beach. Store signs blurring away as Joel yells from a car window.

When the opening chords chimed as Joel awakes in the new pajamas he doesn’t recognize, and with each tonal transition thereafter, I was struck by how deeply Jon Brion’s score was etched in my mind. A strange thing in itself: the memory of an artist’s work so concerned with memory. From Joel’s childhood, to the frozen river, to the beach in Montauk, the music goes a long way in unifying Sunshine’s patchwork chronology.

Where Malkovich is acerbic, brimming with social satire, Eternal Sunshine has a disarming sense of honesty. It is weird, but its weirdness serves in finding what Werner Herzog likes to describe as the “ecstatic truth.” The timeline aids the same function. There is a deeper current accessed which transcends the social and material circumstances of the characters.

“I don’t think I think about it,” Kaufman answered, when asked about writing for the audience. “And then after I’m done, I’ll show it to somebody and ask them if it makes sense. And then I go, ‘Cool.’ I think I’m doing what I like. I’m not building a product in my mind, I’m trying to write something that interests me. I don’t think of it in terms of like, how this is going to get people to enjoy it in the theater. I think I have to enjoy it. And I have to be interested in it. And then I’m assuming somebody else will be at some point.”

By some cosmic miracle, Gondry and Kaufman entirely sidestep what could have been a saccharine ending. We see the beginning, where Joel is a coward, as is his wont. In the end, the two don’t even kiss. The Lacuna interviews play over tape recorders while Joel and Clementine reconcile in a dirty corridor. Every awful thing has been said. They are bare before one another.

According to Kaufman, this defining moment of the film was a last-minute decision on set.

“We were there that night at the apartment building, and [the scene] wasn’t satisfying to us, so I went off and wrote this. And we liked it. And the studio didn’t want us, they were trying to force us to make it big, make it bigger, make it certain. They wanted it outside, not in the hallway, because an ending should be expansive, as opposed to in a dingy hallway. But Michel and I didn’t agree with that. So we didn’t do it.”

Both of the films, however different, chronicle uncertain characters submitting to an uncertain experience, and through it, finding a species of truth. And though Kaufman delights in depicting himself and his analogues as spineless and equivocating, neither film would exist without Kafuman’s clarity of vision, and his unwillingness to bend.