Ancient Greece had The Iliad, Rome had The Aeneid. India has the Ramayana. There’s Gilgamesh and Beowulf and Paradise Lost. National epics like these tell us the myth of a people’s founding. Our national myths show us who we are by telling a story about where we’ve come from and where we’re going.

Traditionally these myths came in the form of epic poetry, but a national myth can be told in any medium, even in that most American of artforms: cinema.

In the past century, filmmakers have examined the myth of America from many angles, focusing on different time periods or archetypal characters – the cowboy, the self-made businessman, the immigrant, the rebel. Yet however varied their approach, American epics have recurring themes: religion, money, politics, and masculinity.

Interestingly the greatest American epics are typically tragedies in which the promise of America goes unfulfilled.

Here I present five mythic masterpieces, any of which could be considered the Great American Movie. They’re also about cinematic history itself, and the way we have represented ourselves, to ourselves, on screen.

Arranged chronologically by historical setting, the films constitute a mythological journey through the American soul.

The New World

The story of America begins, of course, before the founding of the United States per se. Set in the 17the Century age of exploration, The New World (2005) is a self-conscious exploration of the American national myth. In the film’s first lines writer-director Terrence Malick invokes the Muse like a classical epic: “Come, Spirit, help us sing the story of our land.” As a film The New World is a monumental work of American transcendentalism that feels like it stands alongside Melville and Hawthorne, Thoreau and Whitman. Using his unique lyrical filmmaking style, Malick tells the story of America as a poetic lament for a road not taken.

Malick reminds us that America is the child of European adventurers and the indigenous peoples they encountered. In The New World the Native princess Pocahontas (Q’orianka Kilcher) stands in for America’s mother. She longs to create a transcendentalist utopia with idealistic explorer John Smith (Colin Farrell). When his restless searching takes him further west, she settles instead for a humble, hardworking pragmatist John Rolfe (Christian Bale), a tobacco farmer who eschews Romantic dreams of living in nature and cultivates European traditions.

In Malick’s tragic vision the story reflects a missed opportunity to recover the lost paradise of Eden’s innocence. As a “new world,” America represented a utopian chance for Europe to start again, but we looked back to the Old World instead and allowed our wild and free nation to be fenced in by so-called Enlightened civilization. It’s not such a bad life, and at the end of the film Pocahontas seems to still hear Mother Earth speaking through her half-English son; yet Malick suggests there’s so much more to this land than we have yet known.

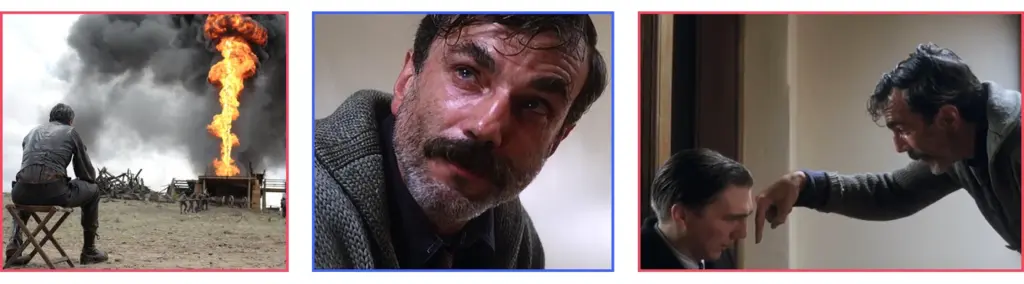

There Will Be Blood

The New World showed us capitalists looking for trade routes and setting up plantations, and it set their quest for money in tension with the philosophical and spiritual promise of a new way of life based on freedom. Three hundred years later, America would still be best represented by an uneasy mixture of money and religion. By the 1920s, the explorers have arrived all the way at the West Coast where their money is coming from oil, and the churches are as wild as the land.

Writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson’s film There Will Be Blood generates a thorough sense of scale for this epic story. It feels as huge, as weighty, as powerful, and as confident as America itself. Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis) is a rugged individualist who almost literally pulls himself up by his bootstraps to build an oil empire in California. So much of the story is told visually in gorgeous painterly cinematic compositions. Plus there’s the viscerally unsettling music by composer Jonny Greenwood of Radiohead fame, and Shakespearean central performances by Day-Lewis and co-star Paul Dano as slippery preacher Eli Sunday. The film’s tone is spot-on: stoic objectivity that feels tough, macho even.

Anderson’s vision of America is one of enormous egos in an openly hostile contest for dominance. Day-Lewis’s oilman and Dano’s preacher manipulate and humiliate each other throughout There Will Be Blood, both sides willing to do anything for power. This is America. The West. It’s California. Los Angeles. There Will Be Blood could be the origin story of any of these. As a nation, we are the fallout from an epic struggle between aggressive capitalism and fanatical religion, and There Will Be Blood sums us up perfectly.

Citizen Kane

When it comes to masterpieces of American cinema, Citizen Kane (1941) stands alone. Set at about the same time as There Will Be Blood (the 1920s and ’30s), Kane follows the flow of Western gold rush money back toward the cultural power center of New York. As a film, it’s just as self-conscious about its role as national epic as Anderson or Malick’s films. The first draft of the screenplay by director and co-writer Orson Welles was titled The American.

Watching it more than 80 years after its initial release, Citizen Kane still feels like it really might be the greatest film of all time. It deftly puts cinema in the same history as Shakespeare and Sophocles and shows drama the way forward. This is the story of America shot in Welles’s youthful expressivist camera style and Robert Wise‘s formalist editing. As a social critique of populist media’s ambition to influence politics, Kane is so clear-sighted it makes Trump seem inevitable. It is also a tragic psychological study of a man who never felt loved. The mysterious “Rosebud” turns out to represent the childhood lost when little Charles Foster Kane’s mother essentially sold him to a bank. The narrative is told from the point of view of Joseph Cotten’s reporter character who functions as a narrator, but instead of voiceover Welles shows us pictures until the film becomes the open secret that explains America to itself.

Of course, it is clear in 2024 that the two big things Welles leaves out of his portrait of America is immigration and race.

The Godfather, Part II

To a degree perhaps even surpassing Citizen Kane, The Godfather (1972) is Shakespearean in scope, psychological realism, and thematic complexity, not to mention aesthetic skill. In his exquisitely crafted film about young war hero Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) and tragic devolution into mafia boss, director Francis Ford Coppola mastered cinema no less than the way Shakespeare mastered iambic pentameter. Then, miraculously, he somehow managed to top himself with The Godfather Part II (1974).

Compared to part one, the sequel is even more epic, which means longer, slower, and more complicated. Part II is paced like a double exposure dissolve, layering history on top of the present. In a critical exploration of the American Dream, the film intercuts the story of Michael learning to navigate the corrupt world of U.S. politics with the story of Michael’s Sicilian immigrant father Vito (Robert De Niro) establishing the family’s mafia-protected olive oil company in New York City. Structurally it depicts the way American business oligarchy evolved out of Old World tribalism and family loyalty. Of course, this episode of the Godfather Saga also ends tragically, showing how the consolidation of power is in fact incompatible with family loyalty. The only reason Michael reluctantly accepted the role of mafia don in the first film was to protect his family, but by the end of Part II his business interests ultimately force him to execute his own brother Fredo (John Cazale).

By the way, the continuation of Michael’s story in The Godfather Part III (1990) is not as bad as its reputation. It’s just not a masterpiece like the first two. And the director’s daughter Sofia Coppola, viciously maligned for her perfectly adequate performance in Part III, gives us a woman’s perspective on the American Dream in Priscilla (2023). This story of Priscilla Presley (Cailee Spaeny), very young wife of the King of Rock and Roll, is not an epic history like the other films on this list. Rather it’s a quiet character study, shot in a chamber style. Writer-director Sofia Coppola lingers on repeated closeups of beauty products and clothes and fashion magazines, thereby framing the story as an exploration of how American culture in the 1950s taught girls to see themselves as accessories to men. It’s like the whole society is conspiring to groom petty young girls for powerful men. Priscilla gets the life every American girl wishes for, and Sofia Coppola shows us why this life not as wonderful as it seems in our fantasies. It’s a feminist take on the dark side of the American dream that serves as a counterbalance to the sort of patriarchal world the elder Coppola explored in The Godfather Saga.

Malcolm X

Writer-director Spike Lee goes beyond counterbalance to a deliver a cinematic counter punch. Like the other films on this list, Lee’s Malcolm X (1992) is a towering masterpiece that stands alongside the great biographical epics of cinema like Lawrence of Arabia or Spartacus. Lee employs the tools of classic cinema to show how Hollywood has shaped America’s image of history (and even how Black people see themselves) while also declaring his film’s place in that tradition.

What better subject for such a confrontational American epic than revolutionary Black-power activist Malcolm X. And what better actor to play Malcolm than young Denzel Washington! Lee cleverly uses Malcolm’s story to stand in for the search for a Black national identity in the context of the trauma of living for centuries under White supremacy in America. It’s less a picture of the American Dream than it is the American Nightmare. The film ends up being an excellent primer on critical race theory and a convincing case for Malcolm X as a martyr for the cause of antifascism.

Like all the films on this list, Malcolm X holds up a mirror to American history. These films show us our national myths and the ways we have failed to live up to the promise of our founding. Tragically the new world’s potential ended up shackled by old world power structures, and our wildness allowed strong men with money to control even our religious hopes for a land of liberty, equality, and justice. It’s kind of a sad story. But if Terrence Malick is right, then the Spirit of our ancestors is still with us, calling us toward freedom even now.