Though 1998’s The Big Lebowski is the Coen Brothers’ film that has achieved the highest cult-movie status, some among us believe their earlier film, Raising Arizona (1987), is the comedy standout. This is especially true for those of us who grew up in Arizona, laughing at its cartoonish send-up of lowlife Phoenix-area yokels seeking an idyllic family unit in their desert trailer home, even if they have to abduct a baby and rob convenience stores to get there.

Loaded with inspired, goofy performances from future Oscar contenders Nicolas Cage, Holly Hunter, Frances McDormand, and John Goodman; breakneck cinematography by Barry Sonnenfeld (later director of Men in Black); and twice as many quotable one-liners as Lebowski, Raising Arizona is a must-see for any aficionado of concentrated, off-kilter quirk.

Shot entirely on location in areas around Phoenix, the movie makes a terrific window into the Arizona experience during the mid-to-late 20th century. But it was inevitable that Joel and Ethan Coen, who grew up in bone-cold Minneapolis, Minnesota, would fall into traps of falsehood like a coyote dodging an anvil and landing in a pile of cactus.

Here are 10 things Raising Arizona gets right and wrong about Arizona.

WRONG #1: No, Arizonans do not (and did not) have Southern accents.

Throughout Raising Arizona, speech is hilariously peppered with idiomatic phrasing and the drawling patterns you’d hear in Texas, Alabama, or Kentucky. For example, Nicolas Cage’s early narration states, “Now, y’all who’re without sin can cast the first stone.” A prison inmate recites a tail of fishing for crawdad (and later eating sand — that’s right), an experience that could only have happened 1,400 miles away, around the Gulf of Mexico (yes, the Gulf of Mexico — not the other name). Holly Hunter’s accent in the movie isn’t far from her natural, Georgia-raised accent, either.

None of the speech patterns make sense to a native Arizonan. Growing up in the 1970s, you were more likely to hear Valley Girl speech from California than anything resembling Texan “Y’alls” or the Faulkner-esque phrasing numerous characters use throughout the movie. Indeed, Arizona’s neighbor New Mexico is practically a dialectic buffer zone that insulates Arizona from any traditionally Southern mannerism.

A speculative explanation is that the Coen Brothers originally may have intended the screenplay to be set much farther east. Dialogue such as “It’s a hard word for the little things,” echoing a line from one of the Coen Brothers’ favorite film, Night of the Hunter (1955), suggests a link to dialect from West Virginia. For those willing to forgive the Coen Brothers’ their stylized indulgences, the Raising Arizona accents are part of the fun, but to a native Arizonan they are so inaccurate as to be perplexing. From all accounts, the Coens hit the linguistic bullseye with their later efforts such as their home-turf based “Fargo.”

WRONG #2: No, an Arizonan would never talk about being “carried off by a twister.”

In another clue the Coens may have intended the film to be set elsewhere, at one point Frances McDormand’s character asks Holly Hunter whether somebody had perished in a tornado. A native Arizonan, especially in the Phoenix area, would be as likely to reference a tornado as a Hawaiian would a blizzard. Though it’s not impossible for a tornado to occur in Arizona, the state gets five or fewer per year. By comparison, states in “Tornado Alley,” such as Kansas and Oklahoma, have 75-100 tornadoes with far more severity. Arizona’s version of a tornado is closer to a “dust devil,” with hot air currents creating quaintly temporary, thin pillars of beige dirt, that as kids we tried to run inside to muss our hair.

WRONG #3: No, banjos and yodeling are not part of the Arizona music experience

Though Arizona has made an epic backdrop for a wide variety of classic Western movies, from Rio Bravo and The Searchers to The Outlaw Josey Wales and Tombstone, few of these movies could explain composer Carter Burwell‘s use of banjos and yodeling for the Raising Arizona soundtrack. The most likely reason for their use? They sound funny (unlike the balloons a character buys in one scene, which don’t blow up into funny shapes, “just circular”). Certainly yodeling does accentuate the emptiness of the Arizona landscape, as well as the goofy spirit of Nicolas Cage’s oft-imperiled character. But it has little to do with Arizona.

Quick Googling reveals that yodeling, which originated in Alpine regions of Europe, was more likely to be found in Mississipi folk and blues music, even if it eventually found its way to the singing-cowboy traditions of some Western movies, or of popular singers such as Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, or Slim Whitman. By the 1950s, yodeling was already on the way out of such genres, with country-western music shifting toward styles of Glen Campbell and Johnny Cash.

Though there were vestiges of country-western style in Arizona culture, such as children being taught to square dance in elementary school (it was actually really fun), most Arizonans of the 1980s were far more attuned to heavy metal, new wave, and California surfer or “cock rock” types of music than whatever Reba McEntire or Randy Travis was singing at the time.

As for banjo, the use of this particularly bluegrass and folk style instrument further shows how much interest the Coen Brothers had in the actual South, rather than the Southwest. They would fully and compellingly indulge this fixation in 2000’s O Brother, Where Art Thou?

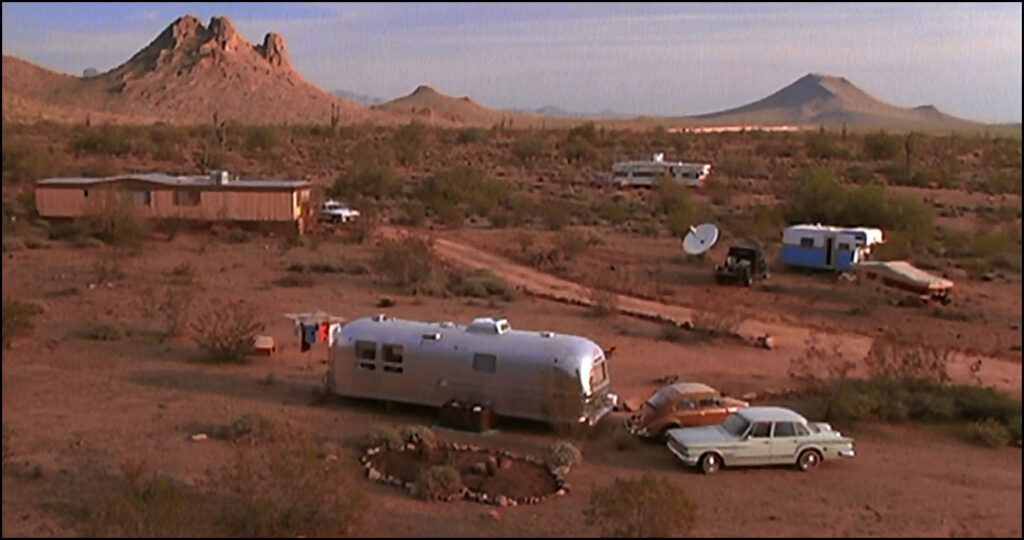

WRONG #4: “Suburban Tempe” does not equate to scattered trailers in the desert.

Most of the mistakes referenced so far are part of the movie’s caricature-driven, creative liberty anyway, but this one is particularly nutty. Nicolas Cage refers to his new home as being in “suburban Tempe” as the movie cuts to a polished-aluminum style trailer in the saguaro-studded middle of nowhere. Tempe, Arizona was (and is) just the southeastern region of the massive Phoenix metropolis. The location used as “Tempe” was actually about 40 miles away, in the Lost Dutchman State Park of Apache Junction, near the Superstition Mountains. To be fair, this could be “suburban Tempe” if you stretch the meaning of “suburban,” and given Phoenix’s rapid development in the decades since the movie was released, the description has caught up with the movie.

WRONG #5: Going barefoot in the desert is a very bad idea.

The poster image for Raising Arizona shows Holly Hunter and Nicolas Cage reclining on lounge chairs as they take in another beautiful Arizona sunset. Hunter sports cowboy boots, but Cage is fully barefoot. Sure, this is a liberty for the sake of characterization, and it’s an iconic visual.

But going shoeless in the desert is a very bad idea. Cactuses. Scorpions. Rocks. Rattlesnakes.

And most of all: Heat. Summer temperatures in the Phoenix area are often in the 100 to 120 Fahrenheit range. The ground absorbs and holds this heat, even overnight. Sidewalk surface temperatures reach 150 degrees, and asphalt often tops 160 — enough to fry an egg. Or cook your feet. Get your shoes on, Mr. Cage.

Those are some of the things the movie gets wrong, but here’s where Raising Arizona nails Arizona:

RIGHT #1: Yes, central Arizona cities are one convenience store after another.

Though Phoenix’s history traces to 1881, not to mention settlement by the native Hohokam 2,000 years earlier, the city’s most significant expansion occurred in the post-WWII era. By 1960, central Arizona became a national draw for retirees (as in the Sun City community) as well as Americans breaking free from the Rust Belt states of the East and Midwest. This rapid development mirrored the rise of convenience stores, which could be quickly established in subdivisions separated by long stretches of grid-like roads.

As a result, driving through Phoenix, then and now, often seems like a Scooby Doo chase scene where the background imagery repeats in an endless loop of strip malls and convenience-store chains.

In Raising Arizona, Nicolas Cage’s favorite robbery location is a Short Stop, filmed at a location on Deer Valley Road and North 23rd Avenue. Older Arizonans might remember a time when there was some variety to convenience-store names, often using alliterative combinations of shapes and letters such as Diamond D, Triangle T, Square S, and Rectangle R. The best-known survivor from that trend became Circle K (don’t ask why it wasn’t “Circle C”….some things are better left as mysteries).

Believe it or not, kids, there once was a time when convenience stores were the exception and not the rule. When Raising Arizona came out, such stores were distinctly emblematic of the Phoenix urban landscape, whereas today we’d expect to find them everywhere but Antarctica.

RIGHT #2: Yes, corny local businessmen dominated Phoenix TV ads.

Raising Arizona‘s plot really gets rolling after Cage and Hunter abduct a baby from furniture-store mogul Nathan Arizona, whose wife’s fertility treatments cause her to have quintuplets. Nathan Arizona was played with mesmerizing gusto by the late Trey Wilson, whom the Coens might have made a star had he not died just prior to production of Miller’s Crossing (1990).

Nathan Arizona’s local success was built, in part, by playing up his homegrown, larger-than-life persona in amateur-level TV commercials. Though Nathan Arizona is fictional, any kid who grew up watching Arizona TV stations was subjected to similar corny dweebs hawking their products.

Real-life characters included Cal Worthington, a Southwestern car salesman whose dealerships extended from Texas to California, and whose commercials fixated on various publicity stunts and “look at me” tomfoolery. Others might remember TV legends Tex Earnhardt, Henry Brown, Debbie Gaby, the furniture-selling Terri Bowersock, or Don Luke from the Bill Luke Chrysler dealership.

My own memories gravitate to Tony Cavolo, a New York transplant who in 1973 started the Peter Piper Pizza chain in the Glendale area adjacent to west Phoenix. Cavolo’s thickly accented tagline, “Come on ovah! …to Petah Pipah Piz-uh!” is burned into the memory of anybody who lived in central Arizona during the last three decades of the 1900s.

RIGHT #3: The movie tips its hat to Bill Rocz, at the time Arizona’s closest equivalent to a Siskel or Ebert.

Raising Arizona opens with a fast-paced expository sequence that hurtles through the Nicolas Cage character’s life of crime and recidivism (“repeat o-ffender!”); how he woos and marries the police officer played by Holly Hunter; their “salad says” of happiness; leading to their hopes and dreams of making a family; then the devastation when she discovers she’s “barren!” because as Cage explains, “her insides were a rocky place where my seed can find no purchase”; the local-news spectacle of a furniture mogul’s quintuplets; and finally, their plan to kidnap one of the babies since its parents “have more than they can handle.” The movie speeds through practically an entire prequel, loaded with cult-classic-worthy comedic moments, in roughly 10 minutes.

Okay. So, as the scenes flash through this onslaught of exposition, we very briefly see a TV news anchor reporting on the Arizona Quints — the babies, one of whom will soon be involuntarily loaned to the desperate infertile couple.

This anchor is played by Bill Rocz, an Arizona media personality who hosted numerous classic-movies programs on KPHO-5, the only TV station at the time completely unaffiliated with a national network. KPHO-5 was also known for a pervasive, sometimes painfully unfunny children’s show called “Wallace & Ladmo.” As far as television went, KPHO-5 represented “Phoenix culture” — a concept usually as barren as the Holly Hunter character’s reproductive system.

Any budding film buff would count on Bill Rocz to offer a wholesome, square, ever-so-smarmy take on Phoenix’s movie offerings. Where popular national critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert offered thumbs, Rocz — pronounced “rose” — granted roses to good movies, complete with rose graphics at the bottom of the TV screen. Better yet, bad movies received stinkweeds, which was funny enough to inspire a local business owner to name her alternative-music store Stinkweeds.

An article in the Phoenix New Times reported that, while on set, Rocz elicited obscenities from the Coen Brothers by asking them explain his character’s motivation. Mostly likely in jest. For those of us who have viewed Raising Arizona repeatedly, the momentary shot of Rocz (who died of Lou Gehrig’s disease in 1996) is a tip of the hat to old-school Phoenix TV days.

RIGHT #4: Yes, trailer homes aptly represent Arizona lifestyle.

The post-WWII expansion of the Phoenix area, not to mention many areas around Tucson, Arizona’s second-largest city, was all the faster because of the ease of building neighborhoods from mobile, or trailer, homes.

Mobile homes were a perfect fit for Arizona’s retirement communities, as they provided an economical option for those with limited pensions or savings. Whereas eastern homes require deep foundations to offset damage from freezing winters, in Arizona homes could be built at ground level with no such problems. The cement-like Arizona soil, called caliche, made digging foundations costly anyway. And zoning laws to preserve the tourist-friendly views meant most homes had to be built at the one-story level.

Under these conditions, mobile-home neighborhoods easily fit into development plans. I remember visiting elderly relatives and family friends in Peoria or Sun City, driving into trailer parks adorned with pink flamingos, painted-white aluminum mailboxes, and brightly colored pinwheels. Friends in nearby Buckeye had expansive, almost luxurious digs in double-wide trailers.

For Raising Arizona to set its family scenes in a trailer home made perfect sense. Many Arizonans grew up exactly how the movie depicts, minus the part where the interior walls are destroyed by escaped prison inmates, of course.

RIGHT #5: Yes, Arizona sunsets are so stunning you can watch them like a show.

The iconic Raising Arizona shot, used as its poster, shows the young couple spending their evening watching a sunset. As the time-lapsed sky’s gradients shift to darker hues, Holly Hunter’s character sums it up as, “That was beautiful.”

The one problem with this scene is it doesn’t do justice to the gorgeous, visually orgasmic spectacle of a true Arizona sunset. Instead, the scene’s sky seems ironically simple, as if accentuating the characters’ undemanding needs. Nonetheless, you really could spend quality time taking in an Arizona view, from its blood reds to astounding purples and daquiri-bright ambers. No peyote trip necessary.

In conclusion: Whether Arizon-accurate or Arizon-erroneous, Raising Arizona deserves a cult-nerd status on part with the best. The Big Lebowski may have its fanatics, but they’re stuck dissecting rugs, sweaters, bowling alleys, and German nihilists. Amateurs! (Meanwhile, Burn After Reading waits in the wings, committing cinematic sins…)