Because the middle of September, 2025 was overloaded with news and political scandal, the passing of Robert Redford got lost in the mix. The firestorm surrounding the killing of Charlie Kirk, the suspension of Jimmy Kimmel’s late-night show, and the ongoing disaster of the U.S. presidency left many unaware that Redford had died. (Many bigger stories also were buried, like the confirmation that Alexei Navalny, a political competitor to Vladimir Putin, died due to poisoning.)

Robert Redford was denied the remembrance his passing merited. He was not just a megawatt star, but an insightful director, a steward for other filmmakers, and a person who didn’t let his celebrity eclipse his integrity. Instead, he wielded his power with focus, often using it to make significant, positive contributions that extended well beyond the movie theater.

Despite his booksmart boyscout’s charm, his athletic Santa Monica surfer looks, and an enviable mop of copper-blond hair, Redford kept his ego at bay with the sureness of a lion tamer training a kitten. In interviews Redford rejected his sex-symbol status, and his work evaporated prejudicial notions about looks and brains being mutually exclusive.

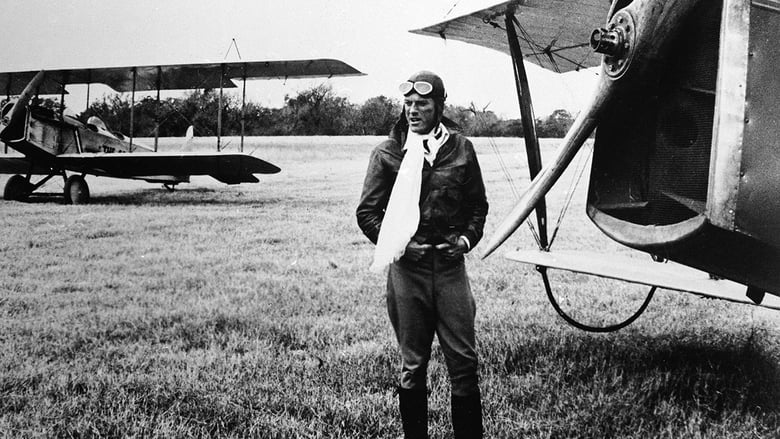

Many of Redford’s biggest roles were dual, alongside other major names such as Paul Newman, Dustin Hoffman, Barbra Streisand, or Meryl Streep. He could carry a movie like Downhill Racer (1969) or All Is Lost (2013), but fit well into ensembles like The Great Gatsby (1974) or Sneakers (1992). He was the preferred leading man for multiple directors, including George Roy Hill, Michael Ritchie, Barry Levinson, and especially Sydney Pollack.

Redford trailblazed the star-turned-auteur path. Few actors have used their understanding of acting craft to direct as intuitively as Redford did for Ordinary People (1992) or Quiz Show (1994). He used his clout to highlight issues he cared about, whether exploring ethnohistorical issues with The Milagro Beanfield War (1988) and Incident at Oglala (1992, as narrator), or connecting the dots behind U.S. military strategy in Lions for Lambs (2007).

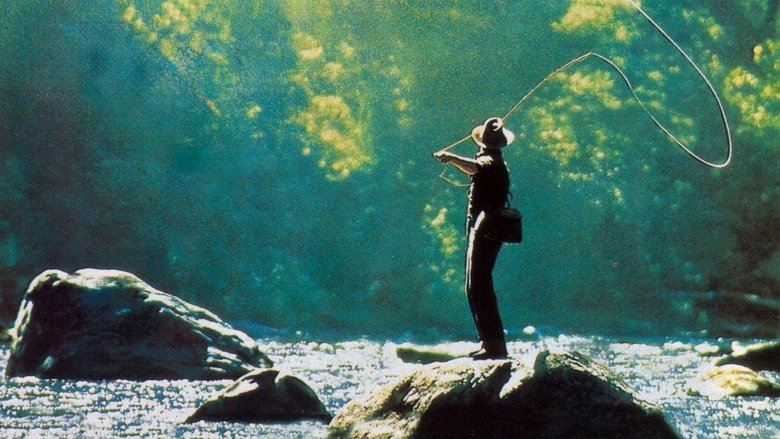

Redford cultivated other people’s careers, symbolically handing off “golden boy” status to Brad Pitt in A River Runs Through It (1992) and Spy Game (2001), while boosting generations of independent filmmakers through his establishment of the Sundance Film Festival (and Institute, Channel, and…) based in Redford’s favored turf: Provo, Utah.

Redford’s films gravitated toward social issues, rarely indulging fantasy or escapism. A side effect is that while he was a white-hot star when making films like The Way We Were (1973) or The Electric Horseman (1979), some of his pictures can seem a little dated. In terms of long-term pop-culture accessibility, it might have worked against him that many of his projects focus on nitty-gritty human details and moral nuances instead of standard genre thrills. Nonetheless classics like All the President’s Men (1976) and Three Days of the Condor (1974) are newly relevant as history echoes itself. Late in his career, Redford gave a nod to escapist entertainment by appearing in Captain America: Winter Soldier (2014) and Avengers: Endgame (2019).

I couldn’t summarize Robert Redford’s career without writing a book, and sorry to say I still haven’t seen many of his lauded works, such as 1980’s Brubaker. Eventually I’d like to see them all; I caught the lighthearted A Walk in the Woods (2015) the other day, when a lot of Redford’s movies showed up in the “trending” feed of a streaming service. Perhaps I’ll watch The Old Man & the Gun (2018) next, or Jeremiah Johnson (1972) again to take in views of Redford’s beloved Wasatch Mountain Range wilderness.

Here are some of my takes on his works, with commentary and recommendations.