[Editor’s note: James DiGiovanna, an award-winning film critic for the Tucson Weekly for much of the 2000s, has put together a list of the 21st century’s greatest films that haven’t received the attention they deserve. He selected so many recommendations, we’ve divided the list into several articles. This is part three, spanning 2011 through 2013.]

Part 3: Best Under-Seen Movies of 2011-2013

Upstream Color (2013)

Usually films that focus on emotional content offer an initial trauma to explain the emotions. But, while Upstream Color does that, it doesn’t make knowledge of that trauma accessible to the traumatized. Instead, we get a movie that is rarely made, a film about how bad it feels to feel bad without knowing why you feel bad.

None of this would work without the heart-piercing acting of Amy Seimetz who delivers the line “something really bad happened to me,” with a kind of layered confusion and force that few actors could pull off. The sense of loss Seimetiz’s Kris and fellow sufferer Jeff (Shane Caruth) have is exasperated by the fact that they not only don’t know what happened, they also don’t know how they’re continuing to be victimized.

There’s a kind of despair, depression, and a blunted hopefulness that come from the universal human condition of being unable to understand why we feel the way we do. The plot can be confusing, and director/writer Caruth wisely offers no exposition, but even if it doesn’t make sense on a first viewing, the story of parasites, dying piglets, a terrifying thief, and an experimental noise musician who knows more about worms than he really should is more than enough to keep you watching and wondering.

Under The Skin (2013)

This is easily Scarlett Johansson’s best performance. There are some terrible, overdone ways that space aliens are portrayed in American cinema, mostly by actors imitating 1950s cinematic robots or by behaving like giant toddlers just discovering the world. Johansson presents an alienness that’s adult, emotive, and alive with repression.

This is vastly aided by Daniel Landin’s eerie, claustrophobic cinematography. The practical effects used to create the extraterrestrial technology makes it seem like something no earthling would dream up, and the sequence showing the alien, umm, consumption device? is both uncanny and morosely beautiful.

There’s also a standout performance by Adam Pearson as a paragon of loneliness who wanders into the alien’s disturbing game of cat and meat farm.

Coherence (2013)

Ever go to a house party with a group of friends and think about what would happen if you wound up in a space-time anomaly that repeated that party in an infinite series of alternate universes? Think how much more intense that would be than being a space battle with an avowedly evil empire that spends all its money on helmet design. Like, instead of faceless hordes, you’re confronted with all the possibilities of yourself that you failed to realize.

The acting in this movie has the kind of precision that only comes from people who aren’t stars and haven’t condensed their emotional range into a small set of facial tics. They seem a lot like human beings. Which is the most terrifying thing to be.

Prince Avalanche (2013)

So that really uptight guy from work who does everything by the book? What if on the weekends he took some oxy and explored rural areas, having hazy encounters with the sort of people you never run into if you don’t get lost in a sea of backyards and color-balanced woods. That’s this, with Paul Rudd showing that if he really wants to, he doesn’t have to do the Paul Rudd Character.

Drinking Buddies (2013)

I like this film because it’s the antithesis of the Kardashians/reality show style of being in the world. So much cinema relies on people behaving overly dramatically to what could be, if handled with complexity, interestingly dramatic situations. Hollywood likes to turn these scenes into absurd and unlikely shouting matches because the director wants cheap emotional content. Which is really just a director’s way of saying “I don’t understand how people really act, or how that could be interesting.”

In Drinking Buddies it’s very interesting. Like, people have reasonable conversations while still being wounded. They do this because they, like most of us, maintain the ability to be concerned about others in spite of not being entirely happy themselves. I’m worried we’re eliminating that as a way of life, so at least Drinking Buddies will be a cinematic preservation of what non-psychopathic human interaction used to look like.

It’s a Disaster (2012)

If the end of the world happened while you were having a dinner party, which of your idiot friends would really screw it up? While comedic, and including some B-list stars, director Todd Berger keeps his movie from the groan-inducing dopiness of most end-of-the-world comedies by aiming small and hitting the target. The apocalypse is terrifying, but so are a bunch of unarmed 20-and 30-somethings trying to work it out while some of them are so rude as to be late for dinner!

What Maisie Knew (2012)

I’m very easily bored. Who isn’t these days. But nothing is more boring to me than action movies where the action doesn’t move the plot. I just don’t care how many bullets are being thrown around. And they’re all shot with that boring blue filter, and there’s really no reason for the action sequences except, I dunno, contemporary Americans just like loud noises or something?

What Maisie Knew is a quiet, slow, gorgeously photographed film. There are actual colors on screen! like you’d see in the real world! Only more carefully arranged. And nobody shoots anybody. And there’s a little girl who doesn’t understand what’s going on, and behaves in the way human children behave when they’re confused and scared but maybe hopeful. Watching it is like being a sad, beautiful place where people don’t need to create drama, because everything we feel, if conveyed subtly and honestly enough, is far more drama than we can handle.

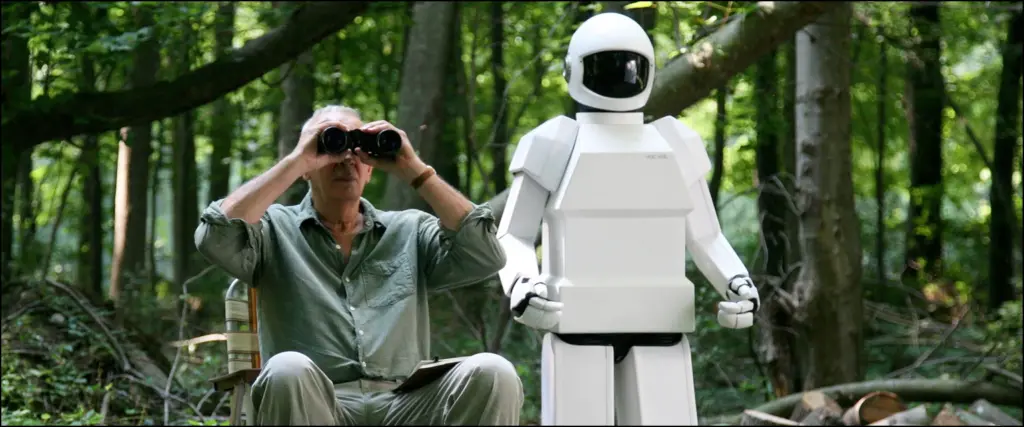

Robot and Frank (2012)

There are a lot of films and tv shows about the relationships between robots and humans, but most of them are both ultra slick and oddly sexualized. Robot and Frank didn’t get the attention that softcore porn stuff like Westworld or Ex Machina did, but it avoids their gratuitous nudity and violence for a quieter, more effectively emotional story. It is, in many respects, a film about memory and consciousness, a theme that’s enhanced by making the robot a non-conscious appliance.

Frank Langella plays an elderly man whose son thinks he needs a fulltime guardian, and so he buys him the latest in robot elder care. Knowing that’s it’s an unthiniking thing, Frank does what we do with any appliance: he yells at it, blames it, and ultimately makes a one-way emotional connection with it. The film takes off when Frank realizes that his robot is not particularly concerned about what is and isn’t legal, leading Frank to look back to an old profession of his.

The movie is sealed with a kick-in-the-head twist with Frank’s relationship to a librarian (Susan Sarandon) that isn’t just for shock value, it’s the moment that ties the whole film together.

It’s Such A Beautiful Day (2012)

Don Hertzfeldt is arguably the best creator of animated films of the 21st century. It’s a Beautiful Day, his only near-feature length piece, is a collection of three connected shorts, Everything Will Be Ok, I Am So Proud of You and the titular It’s Such a Beautiful Life, which presents a uplifting but also devastating ending to the story of Bill, a man with some sort of brain damage who experiences hallucinations, delusions, and amnesias.

Bill’s distorted perceptions and memories are animated entirely through practical effects on a 35mm analog camera, with Hertzfeldt employing light leaks, pinhole effects, collage, re-photographed imagery, and hand-made split-screens. Avoiding digital slickness enhances the sense that our experiences are made by a blobs of fallible neural matter that creates something so immaterial that it actually has feelings, values and hope.

It’s a funny, sad, moving, and philosophically adept exploration of life, death and immortality that has a more natural interiority than any non-animated film has ever achieved.

Martha Marcy May Marlene (2011)

I really do enjoy many of the Marvel movies. If they’d made Martha Marcy May Wolverine it might be my favorite movie of all time. But, other than in the miniseries WandaVision, they waste Elizabeth Olsen’s acting skills. It’s hard to be good when you’re handed the kind of script they gave her in, say, Doctor Strange and the Multiverse of Magic. I mean, she’s fine in it, but if you want to see what she does given a startlingly original screenplay and naturalistic, but still poetic, dialogue, you have to check out Martha Marcy May Marlene.

Olsen plays a young woman traumatized by the time she spent in a tiny woodland sex-and-crime cult led by a soothingly psychopathic rapist (John Hawkes, who would probably be great as Wolverine’s cousin the Appalachian meth dealer.) The drama kicks in when she winds up back in the world, not realizing she lacks social skills or any understanding of sexual propriety. The combination of naivete with a lack of innocence and a surfeit of unrealized confusion that she conveys in every scene has a complexity that alone would make this film great. The soothing cinematography and a plot that handles shock and banality with equal skill seals the deal.

The Oregonian (2011)

I reviewed this on Screenopolis a while ago, so you can check it there, but if you wanna see something that’s about 95% utterly original content, and you’re not averse to recreational drug use, check this out.

Another Earth (2011)

I think this is Britt Marling’s best work, which is saying something. It’s science fiction at its best, where the science fictional element is perfectly placed to show us something about what it means to be shitty little humans on a planet ruled by the kind of vicious blind chance that ruins lives and leaves blame in its wake.

Philosophers call this “moral luck”: the way two distinct punches, of absolutely equal force, thrown at the same target, could, depending on a slight change in the strength of the skull of the direction of the hit, lead either to a mild bruise or someone lying dead at your feet.

But what if both options were to happen at once? Shrödinger didn’t believe the cat could be simultaneously dead and alive, but that’s why most of our entertainment is in the form of fictional narratives and not logic lessons.