Some movies stand up over time. You can watch “The Shawshank Redemption” (1994) or even “Double Indemnity” (1944) and enjoy them as much as ever. Other movies are stuck in a cultural vortex, sucking the presumptions of their era into a black hole of perplexity.

Case in point: “Parenthood,” the 1989 comedy-drama directed by Ron Howard. The film recently became available for streaming on Netflix, ready for a filmographical dig into a bizarre, wrongheaded yesteryear.

“Parenthood” was the baby of Howard and the writing team of Lowell Ganz and Babaloo Mandel. They took the titular theme and threw it around like goblins juggling giggling, pooping babies. The movie has the feel-good sheen of a family-friendly product, where the whole family can go to their local mall (for the younger folk, a “mall” was an enclosed series of stores with their own specialized categories) and see funny people act out scenes of parental frustration and child-rearing mayhem. The movie offers small insights, mirthful scenes of kids vomiting or sustaining mild head injuries, and an overall positive view toward poorly planned procreation.

Examining this artifact carefully, I found it disturbing. At some point, every woman of fertile age has a baby. Dianne Wiest (a sexually frustrated single mother), Mary Steenburgen (an even-tempered housewife who already has three kids), Harley Jane Kozak (dissatisfied wife to a man determined to turn his young daughter into a genius), and Martha Plimpton (a volatile teen with a punkish streak and poor conflict-resolution skills).

The movie’s ensemble-wide happy ending sees each of its several hetero-normative couples proliferating and fertile, with almost none of their pregnancies planned, or mutually agreed-upon with their partners. Kozak’s character violates the trust of her husband (Rick Moranis) by sabotaging her birth control, even though he wants to be a one-child parent. After leaving him, he woos her back by serenading her at her workplace, even though as she says, it “could get me fired.”

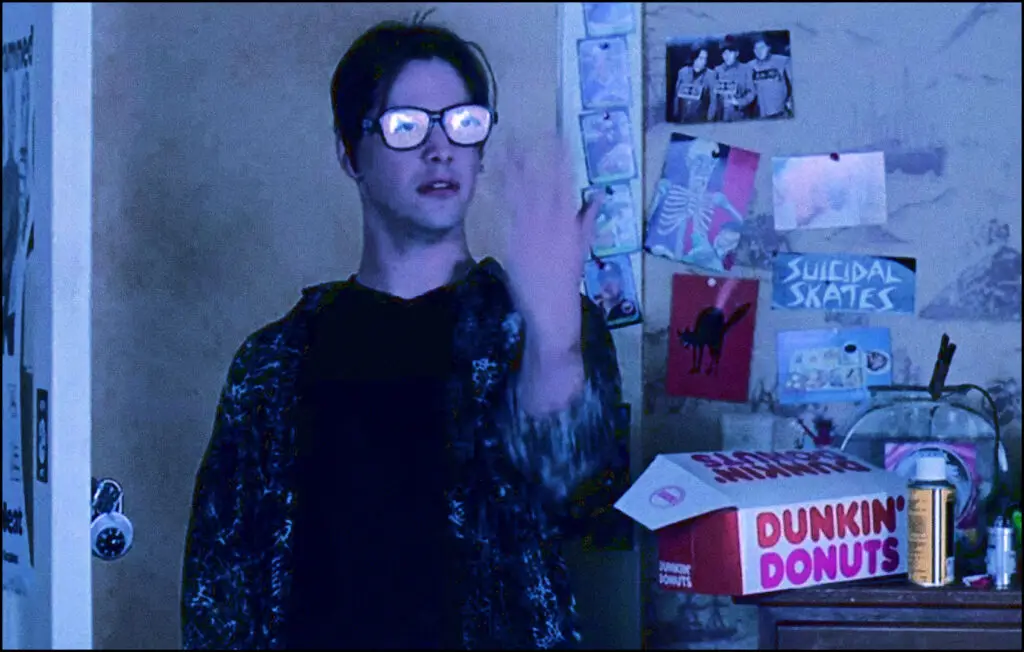

Plimpton’s character, a high school cheerleader, is impregnated by an ever-good-natured Keanu Reeves, who facilitates the movie’s Egregious Product Placement of a non-story-related Dunkin Donuts box. Reeves has few job prospects, and endangers himself as an amateur drag racer, but becomes a surrogate big brother to Plimpton’s younger brother, a budding, porn-curious masturbator played by Joaquin Phoenix (here credited as Leaf Phoenix, with a fresh face far removed from his later “Joker” years).

Wiest, humiliated in an early scene when her vibrator is accidentally shown to a large group of people, eventually gets paired with a biology teacher (not a terribly subtle occupation), and is the movie’s surprise-reveal pregnancy. Why she chooses to procreate, after spending the movie struggling to raise two troubled kids, is one of the movie’s many sub-plots left dangling.

Steve Martin plays the movie’s neurotic center, a dad discombobulated by his clumsy and underconfident kids. Martin has a bitter sense of resentment toward his own father, played by Jason Robards, who seems to favor his black-sheep son, a gambling-debt loser played by Tom Hulce (best remembered as Mozart in “Amadeus” (1984)). Martin’s cutthroat boss under=appreciates him, so Martin quits, only to find that his wife is pregnant (unexpectedly) with their fourth child. With plotting at the simplistic level of a sit-com, the family’s financial crisis is easily averted when the boss inexplicably begs Martin to return to his job.

“Parenthood” is loaded with cute, easy grabs for audience approval, delivering minor gags via very obvious set-ups and payoffs. An early, casual conversation about automotive fellatio leads to a scene of Steenburgen trying to alleviate Martin’s anxiety by surprising him with a blowjob as they drive home. The punchline? He wrecks the car. (The movie never follows up on this; the car is not seen again and, thankfully, the accident does not result in genital disfigurement as it does in another film from the era, “The World According to Garp.”)

The slices-of-life format takes a philosophical turn when a grandma (who, like the muppety children, exists for quick “aww” reactions) mentions her preference for roller coasters over merry-go-rounds. The “life is a roller-coaster, with ups and downs” metaphor could be left for the audience to savor, but instead the metaphor is repeated, characters argue with it, and Ron Howard whacks the metaphor over our heads with a final scene that renders a children’s chaotic school play with the tilting and screaming sounds of an amusement-park thrill ride.

What makes “Parenthood” so unsettling is how it takes the infinitely complex subject of life itself and aims for only the most pat, neat, and happy resolutions. The film is designed as a machine to assuage a positive view toward proliferation and baby-making. Unplanned pregnancy? No worries: Everything will work out as long as you have family and friends. It’s a pleasantly sentimental drug designed to gloss over difficult questions.

Among those questions: Why do none of the characters choose to get an abortion? Why is miscarriage not mentioned? Why are contraceptives almost completely left out of the conversation? Why do the male characters have next to no say in the choice of fertility? The movie of course also avoids mentioning STI’s, abusive relationships, drugs and alcohol, or psychological struggles (beyond what’s easily solved). The story world is almost entirely white, middle-class, and heterosexual, though the story briefly includes a mixed-race (primarily black) child whose parents have both abandoned him, and so is adopted by the elder Robards.

“Parenthood” in no way resembles real life, then or now. Its idealized world might have been passable for audiences in 1989, but now more closely resembles an alien artifact than anything that could exist on earth.