If, like me, you worked up a pretty good Marlene Dietrich imitation as a child after catching The Blue Angel on PBS, belonged to a small but devoted Cabaret cult in high school (Wilkommin!), and still own three different cast recordings of The Threepenny Opera, Babylon Berlin – a gorgeous, upsetting, German-made, music-and-dance-and-cruelty drenched detective saga set in Weimar Germany – is exactly your speed. Go watch it. Now. Many hours of delight and wonder await.

(All four seasons are on the international streamer MHz Choice, available through Amazon for $7.99 a month with a free trial period. MHz deserves credit for the excellent subtitles. Do NOT go for the dubbed version.)

Even if German between-the-wars angst and cultural ferment aren’t one of your special things, you may want to give this spectacularly mounted international hit a whirl. It’s rated 100% Fresh on Rotten Tomatoes, and several critics have declared it the most significant historical production to come out of Germany since Das Boot; some have called it the greatest show ever made for television. I have not seen all the world’s TV shows, but I am inclined to agree.

You need not spend much time deciding whether or not you like it; the mesmerizing title sequence condenses the experience of the show into 30 explosive seconds. Described by its award-winning designer as “a seething energetic fireball” of fragmented images set to a doom-laden, spook-show theme by co-showrunner/composer Tom Tykwer (Run Lola Run), it’s a fair warning of what’s to come.

(The oddly hypnotic end-credits are from a 1921 experimental animation by a filmmaker named Walter Ruttmann, who would later be pushed out of Triumph of Will project because of his “pacifist editing.” Ruttmann died in 1941. Terrible history is the ground this show is built on.)

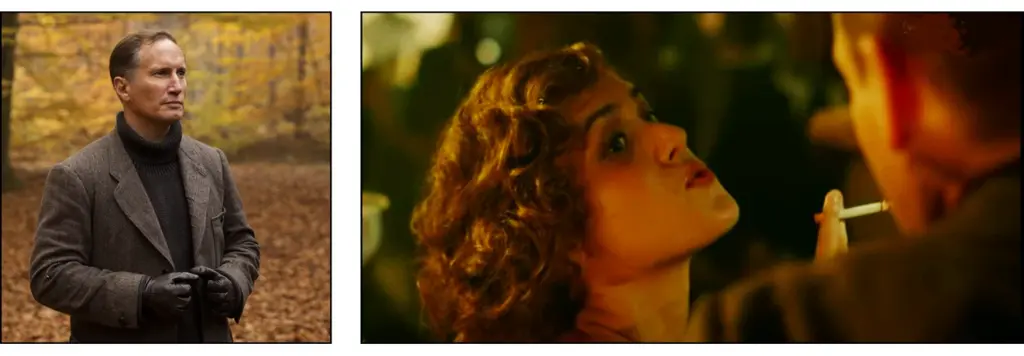

Based on a series of novels by Volker Kutscher, the story follows two deeply appealing central characters. Straight-arrow police detective Gereon Rath (Volker Baruch) and plucky typist / sex-worker / aspiring crime-fighter Lotte Ritter (Liv Lisa Fries) solve crimes, evade death (often), and get concerningly little sleep during the chaotic, artistically fertile final years of the Weimar Republic, 1929-33.

Together, Gereon and Lotte embody the twin disasters that set the stage for WWII. Shell-shocked, morphine-dependent Gereon is haunted by the unspeakable horrors of the trenches (encapsulated by a heart-shattering horse in a gas mask stumbling around a battlefield), while Lotte strains every nerve to escape the squalor and poverty imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles.

Incidentally, the show decisively passes the Bechdel Test, as one might expect from a connoisseur of female agency like Tykwer (as demonstrated in Run Lola Run, The Princess and the Warrior, and Heaven); Lotte has sisters and female friends and colleagues and talks with them about many things besides men.

A host of minor characters and complicated sub-plots, all connected to covert German rearmament and the roiling political stew from which the Nazis arose, entwine around this resourceful, determined pair as they investigate a series of overlapping mysteries: the ownership of a hijacked train loaded with White Russian gold and Soviet poison gas, a series of murders on a film set, and the whereabouts of a fabulous gem stolen from a disappeared Jewish family.

Bablyon Berlin is the most expensive German television series ever made, and every Euro is up there on the screen. The three creator-directors (Tykwer, Achim von Borries, and Hendrik Handloegten) deploy hundreds of extras, thousands of costumes, and dozens of vintage cars to create exciting, naturalistic scenes packed with meticulous detail, intelligent dialogue, and action ranging from horrifying to exhilarating.

The show’s many ecstatic dance sequences — both Gereon and Lotte are dedicated jazz babies — are a pleasurable relief from the thickening darkness. Relief both for us and for the characters.

It’s the rare feature film that manages to sustain the illusion of a former time with anything like this near-tactile quality for even 100 minutes, but Babylon Berlin’s creators have delivered 40 hours of it so far. (The last, fifth season is reportedly now in production.)

There’s vast assurance and craftsmanship at work here, and nothing of the stiff self-consciousness of most period productions — none of the “Oh, look, here comes a lady in costume walking carefully into the frame past a horse and buggy.” Streets and squares teem, cafés are packed, crowds are enormous, and a police riot is truly frightening. Memorable individuals emerge from a crowded background in a way that feels like life. We rarely glimpse the uncanny edges of green-screen or a hazy CGI vista: The production used more than 70 period locations in and around Berlin, evidence of an incredible effort by the location team in a city that, lest we forget, was largely bombed into rubble in 1945.

Of the show’s four extant seasons, Seasons One and Two are a coherent whole set in 1929 with the Russian death-train plot as the through-line. We meet a score of important continuing characters, among them The Armenian (Mišel Matičević), an inscrutable gangster who owns the city’s most lavish nightclub; a respectable war-widow landlady (Fritzi Haberlandt) who’s more than she appears; a fatuous mama’s-boy millionaire industrialist (Lars Eidinger); and most indelibly, Gereon and Lotte’s corrupt, unreadable colleague, Bruno Wolter (Peter Kurth, in a brilliantly subtle performance).

When Bruno’s part in the story ends at the conclusion of Season Two, some vitality goes out of the show. We miss his sly, grounding presence in Season Three, where we get rather too much of the idiotic steel-magnate Nyssan and Gereon’s opportunistic old flame (Hannah Herzsprung). The story stops dead for two highly choreographed orgies – one amounting to semi-porn character-torture of Lotte (whom we love) – and dotes for too long over the nascent German film industry. The main mystery, a confusing, costume-heavy series of murders on the set of a loony Expressionist art-film, feels thin and overwrought. Filmmakers tend to be way more interested in the mechanics of movie-making and the history of their art than the rest of us. (Looking at you, Tarantino.)

But with Season Four the show picks up energy again with the arrival of a tough, vengeful Jew from America, a bit of happiness for Gereon and Lotte, the murderous, Scorsese-like return of The Armenian, and the devolution of Nyssan into pure camp. The Great Depression is in full swing and the story’s reach keeps expanding in a way reminiscent of The Wire. It takes us into new corners of the city: struggling newsrooms, homeless encampments, the orderly homes of the Jewish bourgeoisie, the boys-only clubhouses of the Stormtroopers.

Naturally, we long to tell everyone we like to run for their lives, since the show’s creators have said that the story will end with the Reichstag Fire, only months away in story-time. Major events are dragging the series’ hectic, percolating world down toward the blackest noir of all — the nightmare of the first half of the 20th century, where our most fertile modern myths were born. Without the two World Wars, there would be no Mordor, no superheroes, and, arguably, no modern detective genre. Unspeakable evil looms, titanic crimes cry out for solution.

There’s so much more to say about the series – for example, about the wonderful music. The production features a crack 14-member band formed for the show; their danceable, weltschmerz-laden main theme, Zu Asche, zu Staub (To Ashes, to Dust), charted on the German singles chart. The musical scenes range from a deliriously happy number that quotes Dennis Potter’s transcendent Pennies from Heaven to a punishing and, I suppose, inevitable marathon dance contest. But most of the dancing is about people having a ball in the nightclubs for which Weimar Berlin was famous. One night, Bryan Ferry shows up with his orchestra. Particular love has been lavished on these sequences.

But now we must wait. Will Season Five finally explain why a creepy, scarred-up shrink (Jens Harzer, so unfair to Freud) keeps turning up in Gereon’s tormented dreams? Will Nyssen stop changing his outfits long enough to create the V-2 rocket in the basement of the family schloss, as he’s threatened? Will Wendt (Benno Fürmann), the closeted, scheming ubermensch, succeed in seizing control of the police? And, if he does, will even he manage to survive Hitler’s ruthless scramble to the top?

The characters we worry about, of course, are Gereon and Lotte: are they destined to endure Nazi rule, the Allied bombing campaign, the Red Army’s onslaught and occupation? It’s difficult to picture them anywhere but Berlin, and harder to imagine any escape for them from what is to come. But this is fiction, not history, and so we can hope.