Evil Does Not Exist is an allegory. For what exactly, it’s difficult to say.

Helmed by Ryûsuke Hamaguchi, the writer/director of 2021’s Oscar-winning Drive My Car, Evil begins at much the same pace as Hamaguchi’s prior film. That is to say, slowly. When reviewing his filmography before writing this, I discovered that while still in college Hamaguchi shot his own remake of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris. It’s an ethos that has clearly seen him through.

My question upon beginning the film was how, in a runtime under two hours, a story of this cadence could be told. The answer is something closer to a short story, with the moral complexity and various interpretations of those Russians who Hamaguchi favors.

We are treated at the start with an upward tracking shot through evergreen canopy as the film’s beautiful theme begins to play. Just as we are lulled into the rhythm of the woods, that peace is shattered by the buzz of a chainsaw. The film is littered with these small interruptions: The ways we interface with nature, and with each other, obstructing the natural process.

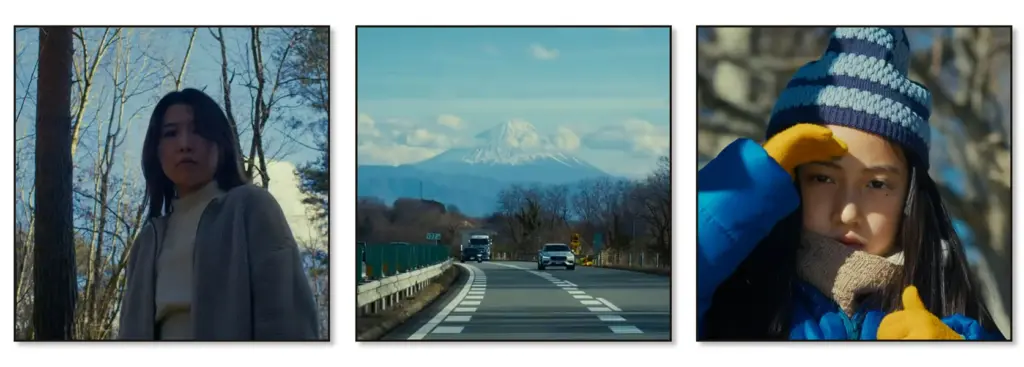

Evil tells the story of Takumi (Hitoshi Omika), a widower and self-described jack of all trades living in a small village in rural Japan with his daughter Hana (Ry Nishikawa). Takumi does odd jobs for the people of the village, such as fetching their prized river water and wild wasabi for the local soba shop. Hana attends the nearby elementary school, and spends her afternoons wandering the woods alone or with her father, who teaches her the names of the trees and how to recognize different wildlife.

Their lives are interrupted when a development company from Tokyo announces plans to erect a new glamping site in the woods near the village. Increased activity could lead to more wildfires and other environmental hazards, and the planned septic tank will introduce pollutants into the groundwater, affecting all villages downstream of the site. Two spokespeople (Ryûji Kosaka and Ayaka Shibutani) are sent on the company’s behalf to negotiate in bad faith with the villagers.

The premise feels trite, but rather than follow the predictable path, the narrative barely moves forward from there. Instead, we get to know the company suits as people, and watch Takumi interact with them. We see in what ways they are different, and similar; we see that the effects they have upon each other are mutual.

Everyone, even the villagers, has been infected by the modern world. However in tune with nature he is, Takumi relies on his hellishly loud chainsaw to chop wood. A young outspoken villager, however cogent, is later seen sucking on a vape. Smoking is ubiquitous, as are phones. Each virtue is undercut in small ways. The villainies, too, are banal and human, however real.

We are constantly caught in this clumsiness of technology as our mediator to the world. A town hall between company reps and villagers requires the use of a booming microphone for each earnest plea and canned response, their voices made menacing by the nature of the medium. A Zoom meeting ends, and the projector stays on as a digital mirror for an office of three. Human communication can barely occur without the use of these alienating instruments.

The film itself is a wonder of digital photography, sunlight dappling the snow and sparkling on the river. This dichotomy works in the film’s favor, and it’s easy to become lost in the deeply saturated hues, the verdant foliage and gleaming blue ice. The camera is a cagey narrator, choosing carefully the arrival and departure of its viewpoint. Often, characters will exit a scene and the camera will linger behind, as though to remind us that nature still exists after we are gone.

Hamaguchi has teamed again with Drive My Car composer Eiko Ishibashi, and her score is (again) the highlight of the film. A memorable orchestral theme repeats throughout, alternating with brief interludes of drums and guitar which echo the modern jazz of Drive My Car. The score is used sparingly, and is all the more magnificent for it. It’s lush, magical, and strange, and I can’t say enough good things about it. Hamaguchi has stated that the primary aim of the film was to create visuals for Ishibashi’s music, and it shows.

Performances are quiet and understated. Omika takes a memorable turn as the stolid Takumi. Previously Hamaguchi’s Assistant Director on 2021’s Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, Omika seems unaware of the camera, a part of his surroundings. Kosaka as the lead company rep particularly shines. His odd relationship to his partner, played by the endearing Shibutani, and his interactions with Takumi and the other villagers, are the character highlights of the film.

From the jump, Evil seems to want us to know something terrible is coming. From its opening chainsaw, to the foreboding carcass of a gutshot fawn, to the distant reports of hunters’ rifles in the woods, grim omens abound. Even so, any viewer would be hard-pressed to anticipate the finale.

I won’t spoil anything here, but Evil’s closing moments are truly baffling. A puzzle is clearly presented to us. Little enough has transpired to that point that the sparse dialogue can easily be combed for clues. There are themes put forward, and obvious parallels to be drawn. Yet I cannot help but think the answer lies in the film’s title.

While I didn’t find Evil as engaging as Hamaguchi’s prior outing, it is a beautifully constructed tale of a smaller order. It’s like a Russian short story put to song, built around the quintessentially Japanese theme of flowing water.