The Brutalist is the epic story of László Tóth, a Jewish-Hungarian architect who arrives in post-war America as a refugee after being freed from a Nazi concentration camp.

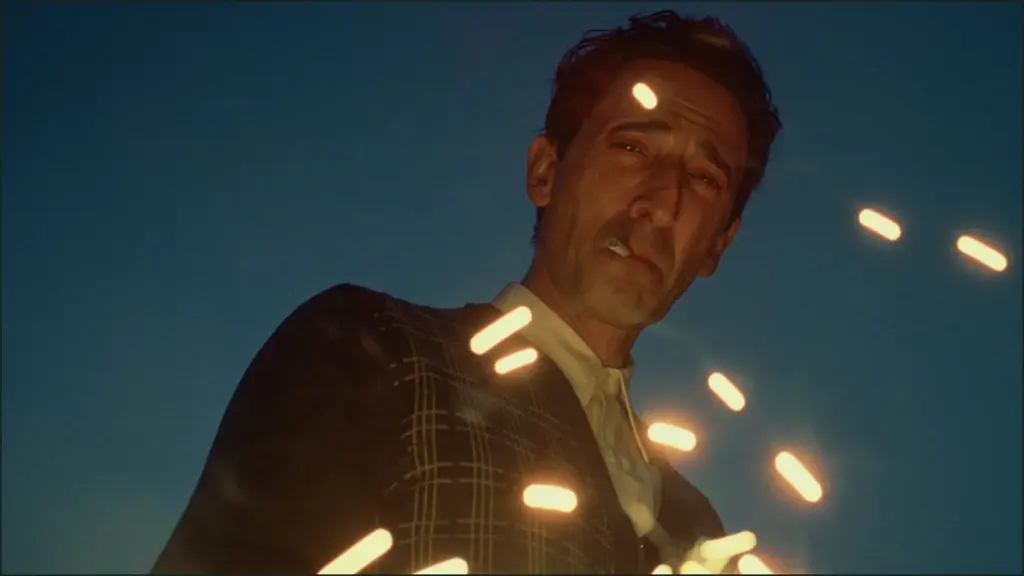

László, played by veteran Holocaust movie actor Adrien Brody of The Pianist fame, is a mysterious, enigmatic character. It’s almost a mild spoiler to know that he’s a successful Bauhaus-trained architect who works in the brutalist style, since his backstory is gradually revealed throughout the entire film with new details about his character still being added in the final scenes.

Despite an improbably low budget of $10 million, director Brady Corbet (Vox Lux) stages the story at a monumental scale appropriate to László’s enormous buildings in size and length: 215 minutes of 35mm Vistavision widescreen. But Corbet often shoots with handheld camera closer than you would expect, giving the sense that you’re standing too close to see the massive edifice before you.

Structured into two acts, the story has at least three distinct thematic pillars that from a distance seem separate from each other but which, on closer inspection, turn out to be connected by a hidden passage. The Brutalist contains within it an American immigrant story, a portrait of an obsessive artistic genius, and a romance. Only in the film’s Epilogue do we see how Art, Love, and Jewishness come together.

Mercifully, the two acts are separated by an intermission, so The Brutalist is not as brutal as you might expect a three and a half hour movie would be.

At the start of the first act László works for his assimilated-immigrant cousin Atilla (character actor Alessandro Nivola) who owns a furniture store in Philadelphia. But it is quickly apparent that the arrogant, pretentious avant-garde designer is not cut out to make dining room sets for the normies who’ve never heard of Architecture Digest and only want the traditional styles hawked in Better Homes and Gardens.

Too proud and independent to work for another architect’s firm, László is at risk of destitution until he meets wealthy industrialist Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce of L.A. Confidential and Memento) who hires him to build a community center in his small Pennsylvania town.

The second half of the film foregrounds the romance plot between László and his wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones of The Theory of Everything and Rogue One: A Star Wars Story) who finally arrives from Europe. László begins construction on the Van Buren building but finds himself wrestling with the financiers who are always trying to cut corners and the locals who are, perhaps predictably, suspicious of László’s unorthodox designs for the community center.

As an architecture style, brutalism is characterized by large scale geometric shapes and minimalist design with bare concrete surfaces. It’s a form of modernism associated with socialist utopian ideals. The Nazis didn’t like modernism because it didn’t seem German enough. It’s too globalist, too forward-looking and not traditional enough. Many Americans agreed.

For his part László describes modernist buildings as “machines with no superfluous parts.” They are just what they are, beautiful and silent. Yet it is hard not to look for allegory and symbolism in The Brutalist. I mean it opens with the image of an upside-down Statue of Liberty and ends with the image of an upside-down Cross. As a work of cinema, it’s too big not to mean something. And Corbet surely does have something to say about the nature of art and the role of immigrants in western countries like the U.S.

In many ways The Brutalist feels like a response to Ayn Rand’s portrait of an uncompromising architect in her novel The Fountainhead. In contrast to Rand’s individualist hero Howard Roark, László depends on others and helps his friends, working hard for the achievement of beautiful goals not for the money and not even for the journey itself but for the production of a lasting work of Art that can inspire social revolution for generations to come.

Whatever else it’s about, the film consistently critiques White Anglo-Saxon Protestants and their so-called “work ethic” that all too often amounts to the worship of money. To build his monumental works László is dependent on the capital of racist and antisemitic millionaires like Van Buren. During a budget dispute László tells a hack consultant that puritanical men like him are to blame for “everything that is ugly, stupid, and cruel” in the world. You might convince them to let you build something beautiful if it flatters their ego and sense of status but they will cut corners wherever possible and, well, screw you over if they get the chance, just to assert dominance and toss you out the minute you embarrass or inconvenience them.

Given that The Brutalist directly links László’s story with the creation of the modern state of Israel and focuses on a Jewish immigrant’s experience, it is perhaps surprising that neither Corbet nor his co-writer Mona Fastvold is Jewish. The film’s perspective on Zionism is somewhat ambiguous, but it seems to me that László sees putting one’s faith in political nation of Israel as a trap. He cites Goethe as saying “None are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe themselves free.” Instead of pretending to establish a utopia, László’s architecture is meant as a reminder that our modern world is built on atrocities, the Holocaust above all.

When Erzsébet first sees the blueprints of the enormous cultural center, she is surprised at how small many of the rooms are yet with very high ceilings — a feature so important László is willing to pay for the extra height out of his own fee. His is a building where we are forced to look up, to see the light high above us, reminding us of the heavenly liberation we have yet to build on earth.

Clearly there is a lot going on in this film. Yet The Brutalist seamlessly joins together all of these disparate elements into a single impressive structure. It’s an ambitious, novelistic tour de force.