This past summer, the children’s movie Inside Out 2 was a huge hit, making more than $1.5 billion. [See the Screenopolis review.] Meanwhile, another kids’ movie, Harold and the Purple Crayon, made barely enough money to buy a deluxe set of Crayolas.

The hapless adaptation of the beloved Crockett Johnson books for tykes, held back from release since early 2023, was bound to perform poorly. Legend has it if you visit the Sony Pictures accounting office where they tallied its box-office returns, there’s just a pile of upturned file cabinets and broken crayons.

Which is too bad because the mere fact that the movie exists makes me happy. My family recently rented it to stream, and it’s as half-baked as expected. But if you eat a half-baked cookie you’re still eating cookie dough, right? (Nevermind the lack of pathogen reduction; this is a metaphor only.)

Call me a Purple Crayon Achiever, or a Crocketeer. Actually don’t. It’s just that I have fond memories of the Harold and a Purple Crayon books, which are among the earliest books my parents gave me, possibly in the crib. (Other early favorites included The King, the Mice and the Cheese; The Berenstain Bears’ Big Honey Hunt; Dr. Seuss’s Scrambled Eggs Super!; and practically half of the offerings in the Scholastic Book Club. And dozens more.)

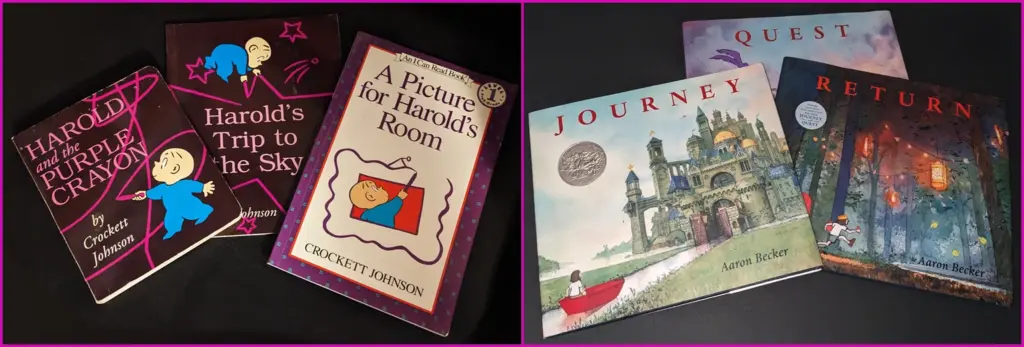

I made sure to get copies of the main Purple Crayon books to read to my own children, because the simple concept and execution is a beautiful representation of creative imagination…and also I wanted to re-read them. Those fat fuchsia lines lead down a primal hallway to my younger, happier self, well before the inexorable transformation to dumb adult.

The movie doesn’t diminish the books. I’ll gladly accept its stumbling, affably sincere tribute to them. It made me think not only of the Purple Crayon books, but of books they inspired. I highly recommend a richly illustrated trio by Aaron Becker called Journey, Quest, and Return, in which a purple-crayoned protagonist explores an alternate universe and meets a red-crayon-wielding friend. Reading these to my kids was an act of interpretation, as they (and the Crockett Johnson books) have no words. For contrast, I’d follow-up with another terrific book with the opposite concept, The Book With No Pictures by B.J. Novak.

There’s a bittersweet transition when kids grow past the read-to-me age. What do you do with the beloved children’s books? Pass them along to other parents, of course. Though be sure to keep a few.

About the movie…

So about the movie: The story has been in stop-and-start stages of development since the 1990s, and it shows. In the books Harold is a four-year-old, bald-ish kid reminiscent of Henry or Caillou (apparently there’s an epidemic of telogen effluvium among cartoon kids), but in the movie he’s grown up to look like The Man With the Yellow Hat from the Curious George books (more favorites — especially that one where George gets zazzed on ether), only in a blue jumpsuit.

Harold’s creative activities are narrated by a voice that sounds unsettlingly like Alec Baldwin, but thankfully turned out to be bedtime-soft Alfred Molina. Suddenly the voice stops, and Harold is confused: Where did his “old man” go? Why did third-person narrative turn first-person? Vaguely aware of his status as a drawing, Harold doesn’t feel he should exist without a father-God. The conundrum reminded me of non-children’s-book The Blind Watchmaker by Richard Dawkins, and I hoped the film would disabuse Harold of the notion that everything must have a designer. After all, he’s the one holding the crayon.

Harold, along with his crudely drawn violaceous friends, a moose and a porcupine, books it out outta there. They draw a door to the real world, step through the glowing amethyst frame, and voila, the animated characters become real humans plopping into a city park like John Cusack dumped onto a New Jersey Turnpike. It’s metafiction for kids!

Harold is played by Zachary Levi, whose face looks like what you would get if you told an AI program to merge John Krasinski with Jason Sudeikis through a “videogame cutscene” filter. Harold’s moose friend also turns human, as played by Lil Rel Howery, whose comic-relief heroism was a highlight of Get Out. (Howery’s role as “Moose” is uncannily close to Kevin Hart in Jumaji: Welcome to the Jungle (2017), who even had a similar nickname, “Mouse.”)

Finally, the porcupine transforms into gothy-fun Tanya Reynolds, who has no quills but plenty of human frills. Those include periwinkle-streaked hair adorning tea-saucer eyes mounted on a Modigliani flamingo neck, in totality reminding me of the Dead Milkmen’s song “Punk Rock Girl.”

The city they’re in appears to be Providence, Rhode Island, but thankfully the local-based Farrelly Brothers filmmakers aren’t involved — let’s stay kid-safe. (Instead, the film is directed by Carlos Saldanha, veteran of several animated Ice Age and Rio films.) Porcupine gal gets lost, and after Harold and Moose draw a bicycle, they’re nearly plowed down by Zooey Deschanel in a station wagon. Deschanel’s character is similar to the one she played in Elf, when she helped fish-out-of-water Will Ferrell adapt; this time she’s mom to a fatherless middle-schooler played by Benjamin Bottani. Guiltily, Deschanel lets the clueless man ‘n’ moose-man stay in her house’s spare room, because if she cared about “stranger danger” the film wouldn’t have a plot.

Harold and Moose befriend the kid, which is convenient because he has a tulpa (imaginary friend) and they have the potential means to scribble it into existence. First he’s going to help them with their quest, which mashes together elements of Stranger Than Fiction (again with the Will Ferrell connections) and P.D. Eastman’s book Are You My Mother? (another childhood favorite). Eventually their creator search leads to a local library, where the supervisor, a haughty dork played by Jemaine Clement, leads them to discover that Harold and the Purple Crayon is a fictional series by Crockett Johnson. When they trek to Crockett’s house-turned-museum in Connecticut, they go into existential crisis (but, you know, for kids) upon learning Crockett went to heliotrope heaven in 1975. Bummer.

I wish Harold and the Purple Crayon hadn’t been so derivative, especially in scenes at the Ollie’s chain store where Zooey Deschanel works. She has an overbearing boss similar to the one Jennifer Aniston had in Office Space (for a moment I thought he might demand she wear more “flair”). When Harold steps in to cover her shift, all heck breaks loose, but it’s uninspired heck: A child in a coin-operated, mini-helicopter flies above the aisles after Harold draws it a set of rotors. As with the outdoor scene of a chrome-and-purple turboprop plane, I worried about kids’ proximity to spinning blades. Can Harold draw a purple emergency room?

Like Christopher Nolan’s Inception, the setup allows for absolute creativity but metes it out in tiny increments. Inception’s dreamworld set rigid internal constraints, leading to fairly standard gunfights. The results of Harold’s crayon are similarly limited: A purple spare tire here, a purple skateboarders’ slope there. It’s sweet how Harold draws Deschanel’s character a purple grand piano so she can resume her performing-musician dream (what is this, The Fabelmans?). But why not draw a purple Crockett Johnson to replace the missing narration that prompted his journey? Why not make this a kid-friendly Reanimator?

One of the things I loved about the original, 1955 book was the way Harold drafted edges of a street extending to a vanishing point, and was then able to walk into it, shifting dimensions. The way it bent reality made the story magical. The movie misses that, but I’ll give it credit for a fun showdown at the end, when Harold squares off against Jemaine Clement’s character, who has broken a part of the crayon for himself. With both armed like wax-wielding gunslingers, you can easily guess one will issue a challenge to “draw.”

The movie has a satisfying but basic ending. I wish they’d gone a little further; Porcupine deserves a worthy subplot to match Reynolds’s comedic potential. Clement’s frustrated librarian, played with the actor’s typically wonderful Kiwi quirk, merits a fuller story too. He comically suffers rejection from Deschanel (another callback to one of her earlier films), and fares little better with a princess brought to life from his Tolkien-aspiring “Glaive of Gagroh” fantasy series. Dang. Crayon-blocked.

All in all, Harold and the Purple Crayon is perfectly agreeable if you draw yourself low expectations.