Alfred Hitchcock was a supremely talented filmmaker. The Psycho director really was a sorcerer of sorts. His ability to craft tension by playing with expectations kept him several steps ahead of the audience.

But there is more to the auteur’s legacy than suspense. In the documentary My Name Is Alfred Hitchcock, writer/director Mark Cousins explores six prevalent themes in Hitchcock’s work.

The picture features a posthumous Hitchcock as its narrator. British voice actor Alistair McGowan’s impersonation is so eerily spot-on that I initially was horrified it might be AI-generated. McGowan captures the timbre, cadence, and mannerisms of Hitchcock’s voice as he comments clips from the director’s filmography, giving the viewer something to latch onto in the absence of any talking heads. (If you do want talking heads, try Joel Ashton McCarthy’s 2021 documentary I Am Alfred Hitchcock, and be wary of its confusingly similar title.)

My Name Is Alfred Hitchcock takes an exhaustive look at the subject’s career while avoiding the pitfalls of similar docs. This is no chronological regurgitation of Hitch’s Greatest Hits. Instead, Cousins focuses on a series of cinematic themes I’ve not seen discussed elsewhere at great length.

The core devices examined here are escape, desire, loneliness, time, fulfillment, and height.

Those six themes are present throughout the majority of the director’s output. Cousins’ written narration, delivered by McGowan, contextualizes them within the director’s personal life, speaks regarding their onscreen implications, provides commentary on the techniques in play, and shares the director’s process for getting inside the mind of the audience.

The first theme to which the posthumous Master of Suspense speaks is how needing to escape plays out in his films. Everyone has wanted to escape from somewhere, something, or someone. Hitchcock told stories about characters seeking escape within films designed so that audiences could escape.

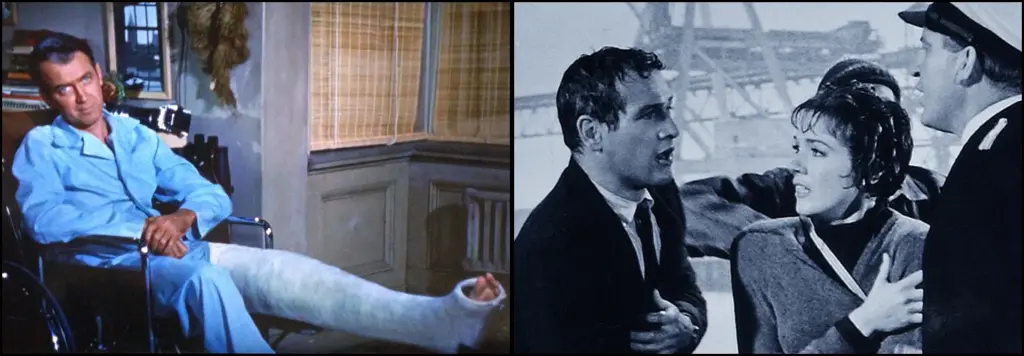

In Rear Window (1954), L.B. (James Stewart) is trapped in his apartment, unable to live the globe-trotting life to which he is accustomed. His interest in the mystery across the way stems largely from his need to escape his four walls. In Torn Curtain (1966), Michael (Paul Newman) and Sarah (Julie Andrews) are desperately trying to escape back to the US from behind the Iron Curtain. In their case, fleeing is their only hope to stay out of prison. Their daring exit is thrilling and marks one of my favorite uses of escape in any Hitchcock film.

Most of Hitchcock’s pictures feature escape in one form or another. Sometimes, it’s an attempt to escape an oppressive government. In other contexts, it may be about escaping daily life. Depending on the setup, escape may correlate to excitement, relief, or regret. Hitchcock used escape to invoke a variety of different reactions from his audience.

During this segment, the narrator of the doc playfully speaks to his favorite type of escape as the onscreen demise of a character and discusses one of the most breathtaking death scenes ever lensed in the process. It’s in Topaz. If you haven’t seen it, the film has some pacing issues and runs too long, but still has ample merits. The death in question being one of the most noteworthy.

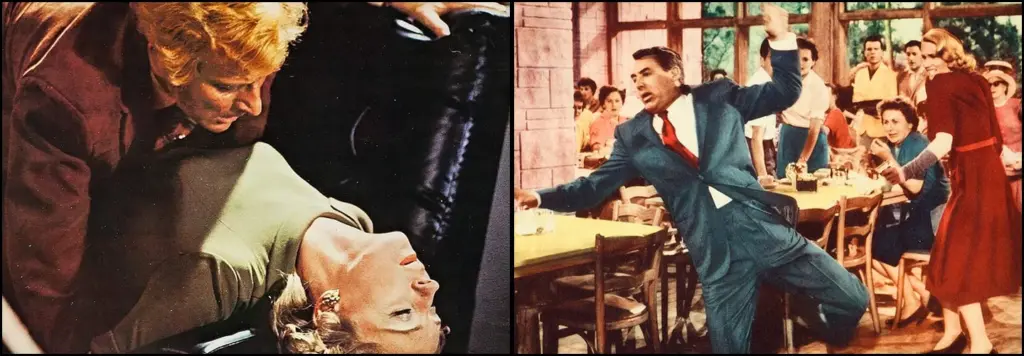

The nature of desire is the next Hitchcockian device explored within the doc. Throughout his career, Hitchcock’s characters have piqued our curiosity with hints of desire, like the implied sexual tension between Brandon (John Dall) and Phillip (Farley Granger) in Rope (1948). Hitchcock has used desire to titillate, as we see with Roger (Cary Grant) and Eve (Eva Marie Saint) in North by Northwest (1959). In Frenzy (1972), he showed us the ugly side of desire. Desire is a constant theme across the director’s work. I suppose that shouldn’t be a surprise. It works in a variety of contexts and almost always intensifies the narrative.

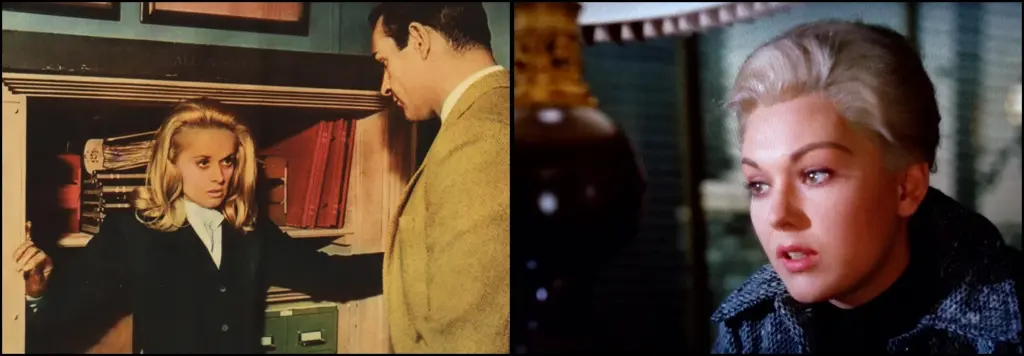

Next, Cousins steers the discussion to loneliness. The narrator waxes philosophical on Hitchcock’s use of lonely women, taking care to explain how he framed his shots to invoke feelings of empathy for his characters’ unfulfilled desire. Loneliness permeates much of the director’s filmography. Many of his female characters are written as lonely, aloof, or otherwise distant. Marnie (1964), North by Northwest, and Vertigo (1958) all feature mysterious women with plenty of secrets, each of whom seems lonely in her own way.

As the documentary progresses, Cousins shifts to Hitchcock’s use of time. He gives context on how Hitch played with time in his films, explaining that the director would sometimes try to slow down time when a character was attempting to speed it up. There’s a nerve-shredding example of that in Dial M for Murder (1954). When Tony (Ray Milland) is out playing poker, his watch stops, creating an impossibly tense experience for the audience. Tony panics, likely leading to a similar reaction from the viewer. That sequence marks a profoundly effective use of time.

Hitchcock has featured time in many ways across his films. We’ve seen characters racing against time, often with an ever-present reminder, like a ticking clock, or metronome. In the case of Rope, the events of the film play out in real time. That lends an immersive quality to the picture and marks a very effective use of that theme.

Next up is fulfillment. Fulfillment is explored throughout the director’s pictures in several ways. The most common may be through two characters coming together romantically at the end of a film. In Rope, we see fulfillment of a different kind, however. The doc touches on fulfillment in that context and recalls how Rupert (James Stewart) has his eyes opened to the evils of the world by virtue of his own careless actions.

Like many of the themes explored in the doc, Cousins finds creative avenues to juxtapose examples of fulfillment alongside cheeky commentary from the Master of Suspense. It’s enchanting to hear such a spot-on portrayal of the late director. And his wry wit helps jazz up some of the dryer subject matter.

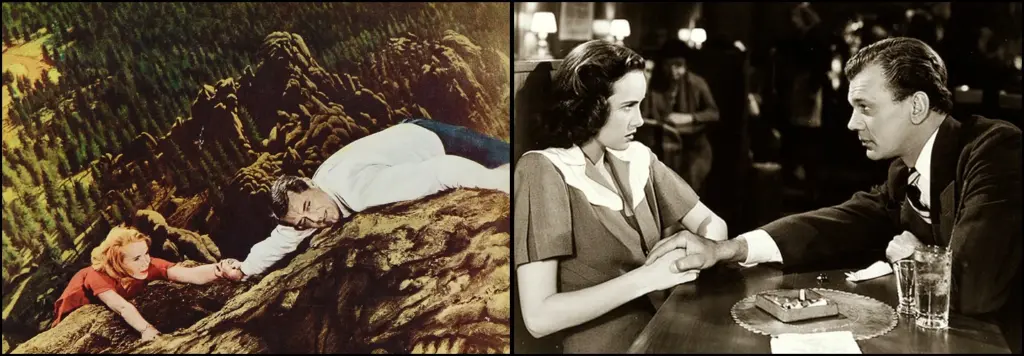

In the last segment, the late filmmaker speaks to one of his personal favorite themes: height. We see height used in the final scene of North by Northwest as Roger (Cary Grant) and Eve (Eva Marie Saint) dangle off the top of Mount Rushmore. That’s a nerve-shredding sequence that uses height to invoke a sense of utter terror in the audience. But Hitchcock used height for many different reasons beyond just inducing viewer discomfort.

Cousins explains how the auteur filmmaker could capture a shot from the very same elevation and angle to convey a bevy of different emotions that mirrored a character’s state of mind. We see this in Shadow of a Doubt (1943) with Charlotte (Teresa Wright) as she comes to realize her uncle (Joseph Cotten) isn’t the man that she thought he was. As the narrative progresses, Charlotte becomes increasingly distant from those she loves most, which is accented by far-off, isolating camera angles likely to invoke empathy for her.

Hitchcock used height more effectively than most. And it’s a device that recurs in almost all of his films. He understood the endless potential it provided for capturing the perfect shot, terrifying, the audience, or conveying a feeling or emotion.

On the whole, My Name Is Alfred Hitchcock is an exhaustive and informative tour through some of the celebrated director’s favorite narrative themes. Mark Cousins does a phenomenal job of showing a different side of a filmmaker who has been studied endlessly. If you’re curious to check out My Name Is Alfred Hitchcock, you can find the film playing select theaters now.